African Nova Scotians

Pre-Planter or French Period (1604-1758)

African Nova Scotians have been in the Bay of Fundy area since Mathieu da Costa was an interpreter between the Mi’kmaq and Samuel de Champlain around 1604. Slaveholding in Nova Scotia dates back to the French colonial period, with about 350 enslaved Africans among the inhabitants of Louisbourg. In 1750, about 13% of Halifax’s population were enslaved Africans.

Planter Period (1760 to 1781)

New England Planters, arriving in the 1760s, brought hundreds of enslaved Africans with them. At least three of the early 1760s grantees of Newport had “owned” enslaved Africans. The 1767 Newport Township census lists an African woman and girl, brought from Scituate, Massachusetts by William Haliburton’s family. In 1774, Haliburton offered a 4-year old enslaved boy named Prince as surety in mortgage negotiations, and in 1779 Haliburton sold enslaved Fillis to the West Indies for £35 (States, “Presence and Perseverance: Blacks in Hants County, Nova Scotia, 1871-1914”). That same year in Windsor, Joseph Northrup sold enslaved 'Mintur' to John Palmer. Reverend Breynton of St Paul's Anglican Church, Halifax, sold enslaved 'Dinah' to Peter Shey in 1776. Henry Denson of Falmouth ran his estate with five to sixteen enslaved people in 1770.

Loyalist Period (1782 to 1807)

In the 1780s, Loyalists brought at least 1,500 enslaved Africans to Nova Scotia and New Brunswick. Some of the enslaved men, women, and children worked on farms, orchards, in construction, in domestic servitude, and skilled trades, including ship-building, in Falmouth, Newport, Summerville, Windsor, Rawdon, and Douglas. In the 1790s, there were 22 enslaved Africans living in Newport and Kennetcook. Nine enslaved people worked at the property of Captain John Grant in Summerville. A Newport history written in 1932 talks of residents visiting the former sleeping quarters of enslaved Africans who tended horses at the stage coach inn at Newport Corner. Image; Public Archives of Nova Scotia

At the same time, about 3,500 Black Loyalists freed for their service to the British in the American Revolution arrived in Atlantic Canada in 1780s. Most received little or none of the land they had been promised, and in 1791 over 1,000 Black Loyalists boarded 15 ships in the Halifax bound for Sierra Leone in West African, where they are referred to, even today, as Scotians. 600 Jamaican Maroons came to live in Nova Scotia in 1796 and were hired as engineers to construct the Citadel at Halifax, but disillusioned with conditions here, four years later, they also departed for Sierra Leone.

Black Refugees (1813-1834)

After fighting for the British in the War of 1812, about 2,000 Black Refugees arrived in Nova Scotia, many from the Chesapeake Bay area of Virginia and Maryland. Many of today’s African Nova Scotians descend from this group of immigrants. The majority of Black Refugees were given “licenses of occupation” instead of grants for poor-quality 10-acre lots that could not produce enough crops for a family to survive. Since they did not own the lands they lived on, neither could they sell the land to move to another part of Nova Scotia. It was not until 2019 that deeds for some of these lands (30% in one community) were granted.

In communities including the Windsor Plains area, Black Refugees worked in many trades, farmed, quarried gypsum, and established a school and a church, which still serves the community. When the Black Refugees arrived, slavery was still practised. While Black Refugees carried a certificate of proof of their freedom, they suffered discrimination and under-employment, and were vulnerable to mistreatment and loss of their treasured liberty. In 1817 Lieutenant Governor Lord Dalhousie recommended that the Refugees be returned to their owners in the United States or sent to Sierra Leone.

Before slavery was abolished throughout the British Empire in 1834, African Nova Scotians contributed skills, knowledge, and labour under dreadful conditions that enriched “owners” and communities. Treatment of enslaved people was harsh, with lashing and hanging used as forms of punishment. Some were sold to the West Indies, families were divided through sale, and some were tricked into life-long indentures, while others were maimed or slain. Many attempted to escape slavery and poor treatment by running away; runaways were advertised in the Halifax Gazette, with rewards offered for their return. Others sought relief through the courts. The formal abolition of British slavery did not end Nova Scotians’ connections with slavery, and the last known slave-ship to transport Africans into the U.S. in 1860 was captained by Nova Scotian-born William Foster. The last survivor of this slave-ship, Cudjo Lewis, died in 1935.

Legacy

Despite centuries of discrimination and hardship, African Nova Scotians have contributed immensely to the economy and culture of Nova Scotia, developing their own African Baptist churches, schools and benevolent societies, which led to the establishment of many vibrant communities. Settlements at Preston, Hammonds Plains, Beechville, Five Mile Plains, Beaverbank, and Prospect Road can all be attributed to the strength of Black Refugees.

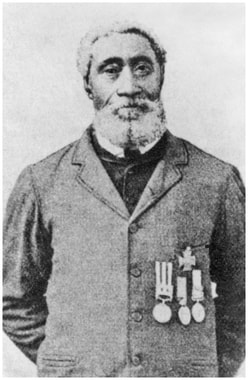

In 1859, William Hall of Horton Bluff on the Avon River, the son of Black Refugees from Maryland, became the first Black and the first Canadian sailor to receive the Victoria Cross. Charles Spurgeon Fletcher, a Windsor native and a uranium expert, became Harvard University's first professor of African descent around 1935. Dr. George Elliott Clarke, Canadian Parliamentary Poet Laureate (2016-2017), among other notable people, comes from Windsor Plains.

African Nova Scotians have been in the Bay of Fundy area since Mathieu da Costa was an interpreter between the Mi’kmaq and Samuel de Champlain around 1604. Slaveholding in Nova Scotia dates back to the French colonial period, with about 350 enslaved Africans among the inhabitants of Louisbourg. In 1750, about 13% of Halifax’s population were enslaved Africans.

Planter Period (1760 to 1781)

New England Planters, arriving in the 1760s, brought hundreds of enslaved Africans with them. At least three of the early 1760s grantees of Newport had “owned” enslaved Africans. The 1767 Newport Township census lists an African woman and girl, brought from Scituate, Massachusetts by William Haliburton’s family. In 1774, Haliburton offered a 4-year old enslaved boy named Prince as surety in mortgage negotiations, and in 1779 Haliburton sold enslaved Fillis to the West Indies for £35 (States, “Presence and Perseverance: Blacks in Hants County, Nova Scotia, 1871-1914”). That same year in Windsor, Joseph Northrup sold enslaved 'Mintur' to John Palmer. Reverend Breynton of St Paul's Anglican Church, Halifax, sold enslaved 'Dinah' to Peter Shey in 1776. Henry Denson of Falmouth ran his estate with five to sixteen enslaved people in 1770.

Loyalist Period (1782 to 1807)

In the 1780s, Loyalists brought at least 1,500 enslaved Africans to Nova Scotia and New Brunswick. Some of the enslaved men, women, and children worked on farms, orchards, in construction, in domestic servitude, and skilled trades, including ship-building, in Falmouth, Newport, Summerville, Windsor, Rawdon, and Douglas. In the 1790s, there were 22 enslaved Africans living in Newport and Kennetcook. Nine enslaved people worked at the property of Captain John Grant in Summerville. A Newport history written in 1932 talks of residents visiting the former sleeping quarters of enslaved Africans who tended horses at the stage coach inn at Newport Corner. Image; Public Archives of Nova Scotia

At the same time, about 3,500 Black Loyalists freed for their service to the British in the American Revolution arrived in Atlantic Canada in 1780s. Most received little or none of the land they had been promised, and in 1791 over 1,000 Black Loyalists boarded 15 ships in the Halifax bound for Sierra Leone in West African, where they are referred to, even today, as Scotians. 600 Jamaican Maroons came to live in Nova Scotia in 1796 and were hired as engineers to construct the Citadel at Halifax, but disillusioned with conditions here, four years later, they also departed for Sierra Leone.

Black Refugees (1813-1834)

After fighting for the British in the War of 1812, about 2,000 Black Refugees arrived in Nova Scotia, many from the Chesapeake Bay area of Virginia and Maryland. Many of today’s African Nova Scotians descend from this group of immigrants. The majority of Black Refugees were given “licenses of occupation” instead of grants for poor-quality 10-acre lots that could not produce enough crops for a family to survive. Since they did not own the lands they lived on, neither could they sell the land to move to another part of Nova Scotia. It was not until 2019 that deeds for some of these lands (30% in one community) were granted.

In communities including the Windsor Plains area, Black Refugees worked in many trades, farmed, quarried gypsum, and established a school and a church, which still serves the community. When the Black Refugees arrived, slavery was still practised. While Black Refugees carried a certificate of proof of their freedom, they suffered discrimination and under-employment, and were vulnerable to mistreatment and loss of their treasured liberty. In 1817 Lieutenant Governor Lord Dalhousie recommended that the Refugees be returned to their owners in the United States or sent to Sierra Leone.

Before slavery was abolished throughout the British Empire in 1834, African Nova Scotians contributed skills, knowledge, and labour under dreadful conditions that enriched “owners” and communities. Treatment of enslaved people was harsh, with lashing and hanging used as forms of punishment. Some were sold to the West Indies, families were divided through sale, and some were tricked into life-long indentures, while others were maimed or slain. Many attempted to escape slavery and poor treatment by running away; runaways were advertised in the Halifax Gazette, with rewards offered for their return. Others sought relief through the courts. The formal abolition of British slavery did not end Nova Scotians’ connections with slavery, and the last known slave-ship to transport Africans into the U.S. in 1860 was captained by Nova Scotian-born William Foster. The last survivor of this slave-ship, Cudjo Lewis, died in 1935.

Legacy

Despite centuries of discrimination and hardship, African Nova Scotians have contributed immensely to the economy and culture of Nova Scotia, developing their own African Baptist churches, schools and benevolent societies, which led to the establishment of many vibrant communities. Settlements at Preston, Hammonds Plains, Beechville, Five Mile Plains, Beaverbank, and Prospect Road can all be attributed to the strength of Black Refugees.

In 1859, William Hall of Horton Bluff on the Avon River, the son of Black Refugees from Maryland, became the first Black and the first Canadian sailor to receive the Victoria Cross. Charles Spurgeon Fletcher, a Windsor native and a uranium expert, became Harvard University's first professor of African descent around 1935. Dr. George Elliott Clarke, Canadian Parliamentary Poet Laureate (2016-2017), among other notable people, comes from Windsor Plains.