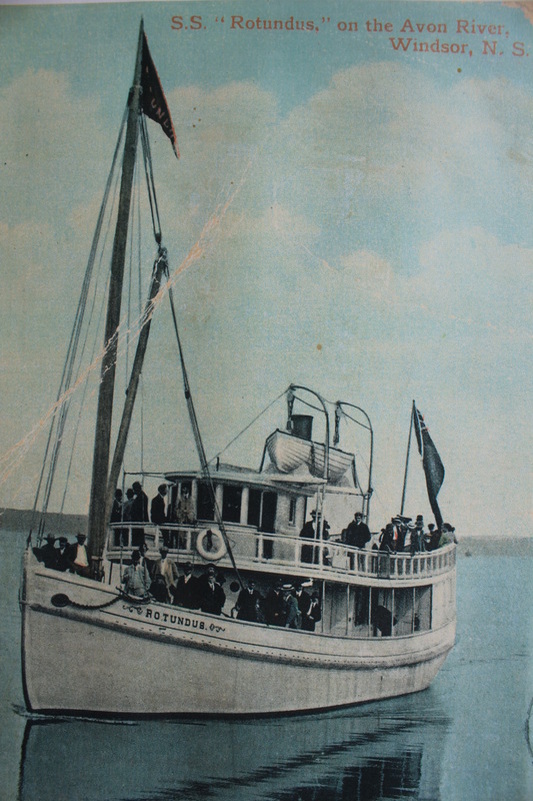

The Steam Ship Rotundus

In 1910, the Churchill Company of Hantsport had given up managing the Avon River ferry services. They were succeeded by a group of Hants County men, whose first project was to search for a boat to replace the waterlogged, aging ‘Avon’, which was no longer considered safe.

At Mackay’s shipyard in Shelbourne they found what they wanted: a boat, unfinished, unnamed and designed for inshore fishing trade. They bought her for $5,000 and christened her Rotundus, derived from the word ‘rotund’ meaning ‘round’. This seemed a fitting name for a boat that was intended to make daily round trips.

The boat was 90 feet long, 23 feet wide and she was shallow. She had two cabins on the lower deck, one for the ladies and one for the men. The only difference between the cabins was that the ladies’ cabin was aft and had the luxury of plush-covered seats. Both cabins had two doors opening onto the lower deck.

The Rotundus had a better engine then the old Avon, whose engine was not equipped with a condenser, resulting in a lot of coal smoke and steam being puffed up with every turn of the cylinder. The Rotundus, however, was not without her faults. Being of shallow draft she rolled easily in a swell, and a rough crossing between Summerville and Hantsport often caused a bout of sea sickness among passengers.

The Rotundus was not fitted with a water tank. Her drinking water was carried in a barrel on the forward freight deck. The barrel was fastened on its side with a square canvas-covered opening on its top side. Above the barrel an enamel mug swung from a spike hammered into the mast at which the water barrel was lashed. To drink from that mug meant sharing germs with all of those who might have drunk beforehand, this didn’t bother the children, though it horrified the mothers.

The Rotundus laid up for the winter, making her last trip of the season about the end of December, unless an unusually early winter had filled the river with ice, causing her to tie up before her usual date. She resumed her trips on April 1st, weather permitting, and the sound of that first whistle blast meant to every inhabitant of Summerville, her home port, that the winter at last was over.

The Rotundus followed a regular schedule on her daily runs. She started in Summerville, went across the Avon to Hantsport and from there she went upriver and back to Burlington, then to Avondale before she reached her destination in the town of Windsor.

For only twenty-five cents, passengers were taken to Windsor for approximately 2 ½ hours before the rising tide signalled the time of departure. If an unusually high tide had covered the wharf, making it impossible for passengers to get aboard, there was a bit of extra time while waiting for the tide to recede and make it safe to cross the planking dry-shod.

The crew remained the same, season in and season out, except for the fact that Fred Lockhart was the first engineer, and that there was a succession of firemen who often left for a sea-going career, leaving their position open for a new man. Many Hants County boys got their first experience in ‘firing’ aboard the old Rotundus. However, Captain Charles Terfry was always Master; Captain Frederick Marsters was mate. Captain Frederick Marsters held deep-water sea Captain’s papers and had been going to sea for many years.

One of Captain Marsters’ duties was to handle the winch when freight was loaded or unloaded. Sometime it was live freight – a pony or a cow, and the good-natured Captain would beckon us to come close to inspect or maybe caress the occupant of the crate before he hoisted it above the deck.

Cole Munro, who succeeded Lockhart as engineer, remained in that position through all the years the Rotundus plied up and down the river. When she was sold, Cole was the only one of the crew to stay with her. It was Cole Munro who trained the firemen. He had a carrying voice, a quick wit and an unforgettable personality. Many young fellows got their sea legs under Cole’s careful teaching.

Told often enough by parents that ‘Mr. Munro’ and ‘Captain Marsters’ sounded more mannerly, the children persisted in the nicknames Colie and Cap’n Fred, neither of which minded in the slightest for both were fond of children.

In 1937, a bus service opened up on the Shore and the Rotundus was sold to William Campbell of Pembrooke who converted her into a tow-boat.

During World War II she served as a water boat in the Halifax Harbour. Then, sold again, she was sent to Sydney, Cape Breton before the war’s end, headed once more for ferry service.

Off the Cape Breton coast she ran into rough weather for which she was not equipped and unfortunately she floundered and sank. The only member of her old crew still aboard was Cole Munro who, during that frightening night, helped to rescue crew members far younger than him, then pulled an oar along with other survivors when they were forced to take to the lifeboats. Cole, favourite to all who knew him, had remained a member of the Rotundus crew until she sank.

At Mackay’s shipyard in Shelbourne they found what they wanted: a boat, unfinished, unnamed and designed for inshore fishing trade. They bought her for $5,000 and christened her Rotundus, derived from the word ‘rotund’ meaning ‘round’. This seemed a fitting name for a boat that was intended to make daily round trips.

The boat was 90 feet long, 23 feet wide and she was shallow. She had two cabins on the lower deck, one for the ladies and one for the men. The only difference between the cabins was that the ladies’ cabin was aft and had the luxury of plush-covered seats. Both cabins had two doors opening onto the lower deck.

The Rotundus had a better engine then the old Avon, whose engine was not equipped with a condenser, resulting in a lot of coal smoke and steam being puffed up with every turn of the cylinder. The Rotundus, however, was not without her faults. Being of shallow draft she rolled easily in a swell, and a rough crossing between Summerville and Hantsport often caused a bout of sea sickness among passengers.

The Rotundus was not fitted with a water tank. Her drinking water was carried in a barrel on the forward freight deck. The barrel was fastened on its side with a square canvas-covered opening on its top side. Above the barrel an enamel mug swung from a spike hammered into the mast at which the water barrel was lashed. To drink from that mug meant sharing germs with all of those who might have drunk beforehand, this didn’t bother the children, though it horrified the mothers.

The Rotundus laid up for the winter, making her last trip of the season about the end of December, unless an unusually early winter had filled the river with ice, causing her to tie up before her usual date. She resumed her trips on April 1st, weather permitting, and the sound of that first whistle blast meant to every inhabitant of Summerville, her home port, that the winter at last was over.

The Rotundus followed a regular schedule on her daily runs. She started in Summerville, went across the Avon to Hantsport and from there she went upriver and back to Burlington, then to Avondale before she reached her destination in the town of Windsor.

For only twenty-five cents, passengers were taken to Windsor for approximately 2 ½ hours before the rising tide signalled the time of departure. If an unusually high tide had covered the wharf, making it impossible for passengers to get aboard, there was a bit of extra time while waiting for the tide to recede and make it safe to cross the planking dry-shod.

The crew remained the same, season in and season out, except for the fact that Fred Lockhart was the first engineer, and that there was a succession of firemen who often left for a sea-going career, leaving their position open for a new man. Many Hants County boys got their first experience in ‘firing’ aboard the old Rotundus. However, Captain Charles Terfry was always Master; Captain Frederick Marsters was mate. Captain Frederick Marsters held deep-water sea Captain’s papers and had been going to sea for many years.

One of Captain Marsters’ duties was to handle the winch when freight was loaded or unloaded. Sometime it was live freight – a pony or a cow, and the good-natured Captain would beckon us to come close to inspect or maybe caress the occupant of the crate before he hoisted it above the deck.

Cole Munro, who succeeded Lockhart as engineer, remained in that position through all the years the Rotundus plied up and down the river. When she was sold, Cole was the only one of the crew to stay with her. It was Cole Munro who trained the firemen. He had a carrying voice, a quick wit and an unforgettable personality. Many young fellows got their sea legs under Cole’s careful teaching.

Told often enough by parents that ‘Mr. Munro’ and ‘Captain Marsters’ sounded more mannerly, the children persisted in the nicknames Colie and Cap’n Fred, neither of which minded in the slightest for both were fond of children.

In 1937, a bus service opened up on the Shore and the Rotundus was sold to William Campbell of Pembrooke who converted her into a tow-boat.

During World War II she served as a water boat in the Halifax Harbour. Then, sold again, she was sent to Sydney, Cape Breton before the war’s end, headed once more for ferry service.

Off the Cape Breton coast she ran into rough weather for which she was not equipped and unfortunately she floundered and sank. The only member of her old crew still aboard was Cole Munro who, during that frightening night, helped to rescue crew members far younger than him, then pulled an oar along with other survivors when they were forced to take to the lifeboats. Cole, favourite to all who knew him, had remained a member of the Rotundus crew until she sank.

En 1910, la Churchill Company d’Hantsport avait abandonné la gestion des services de ferry de la rivière Avon. Ils ont été remplacés par un groupe d’hommes du Hants County, dont le premier projet était à la recherche d’un bateau remplacer le « Avon » en vieillissant et gorgés d’eau, qui n’était plus considérée sûre.

Le chantier naval de Mackay à Shelbourne, ils ont trouvé ce qu’ils voulaient: un navire, inachevé, sans nom et conçu pour le commerce de la pêche côtière. Ils lui ont acheté pour 5 000 $ et lui baptisé Rotundus, dérivé du mot « rotund » signifie « rond ». Cela semblait à un nom approprié pour un bateau qui était désigné pour faire les rondes quotidiennes.

Le bateau était 90 pieds en longueur, 23 pieds en largeur et elle était peu profonde. Elle a eu deux cabines sur le pont inférieur, une pour les dames et l’autre pour les hommes. La seule différence entre les cabines était que les cabines de dames étaient à l’arrière et avaient le luxe des sièges couverts en peluche. Les deux cabines avaient deux portes ouvrant sur le pont inférieur.

Le Rotundus avait un meilleur moteur que le vieille Avon, dont le moteur n’était pas équipé avec un condensateur, causant beaucoup de fumées de charbon et de vapeur avec chaque tour du cylindre. Le Rotundus, cependant, n’était pas sans ses défauts. Étant d’un tirant peu profond elle peut rouler facilement dans une houle, et une traversée rude entre Summerville et Hantsport a souvent causé une quinte du mal de mer parmi les passagers.

Le Rotundus n’était pas cadré avec une citerne. Son eau potable a été transportée dans un tonneau sur le pont des marchandises vers l’avant. Le tonneau était attaché sur le côté avec une ouverture carrée couverte en toile sur sa face supérieure. Au-dessus du tonneau un tasse d’émail se balancé d’un pointe martelé dans le mât au cours de laquelle le tonneau d’eau a été fouettée. Pour boire de cette tasse signifie que les germes sont partagés avec tous ceux qui pourraient avoir bu au préalable, cela ne dérange pas les enfants, bien qu’il horrifié les mères.

Le Rotundus désarmée pour l’hiver, faisant son dernier voyage de la saison sur la fin de décembre, à moins d’un hiver inhabituellement tôt avait rempli la rivière avec de la glace, lui causant de ficeler avant sa date habituelle. Elle a repris ses voyages le 1er avril, si la météo lui permis, et le bruit de ce premier coup de sifflet qui signifie à tous les habitants de Summerville, son port d’attache, que c’est finalement le fin d’hiver.

Le Rotundus a suivi un horaire régulier sur son parcours quotidiens. Elle a commencé en Summerville, a traversé l’Avon à Hantsport et partir de là, elle est allée en amont et retour à Burlington, puis à Avondale avant qu’elle atteigne sa destination dans la ville de Windsor.

Pour seulement vingt-cinq cents, les passagers ont été prises à Windsor pour environ 2 heures et demie avant la marée en montant indiqué l’heure de départ. Si une marée exceptionnellement haute avait couvert le quai, il est impossible pour les passagers à monter à bord, il y avait un peu de temps supplémentaire en attendant la marée à reculer et à le rendre sûr pour traverser le bordé sec.

L’équipage est toujours resté la même, sauf pour le fait que Fred Lockhart était le premier ingénieur, et qu’il y avait une succession de pompiers qui ont souvent quitté pour une carrière de la mer, laissant leur position ouvert pour un homme nouveau. Beaucoup de garçons de Hants County ont eu leur première expérience de « tir » à bord de la vieille Rotundus. Cependant, le capitaine Charles Terfry était toujours maître; Le capitaine Frederick Marsters a été maté. Le capitaine Frederick Marsters tenue des documents de la capitaine de la marine en eau profonde et allait à la mer pour de nombreuses années.

Une des responsabilités de capitaine Marsters était de s’occupé de le treuil lorsque le fret est chargé ou vide. Parfois c’était le fret en vie – un poney ou une vache, et le Capitaine bonhomme serait nous invitent à venir près d’inspecter ou peut-être caresser l’occupant de la caisse avant qu’il a le hissé au-dessus du pont.

Cole Munro, qui a succédé à Lockhart comme un ingénieur, est resté dans cette position toutes les années que la Rotundus plié en montant et descendant la rivière. Lorsqu’elle a été vendue, Cole a été le seul de l’équipage de rester avec elle. C’est Cole Munro qui a formés les pompiers. Il avait une voix qui porte loin, un esprit vif et une personnalité inoubliable. Beaucoup de jeunes gens ont obtenu leurs pieds marins sous l’enseignement attentif de Cole.

Dit assez souvent par les parents que 'M. Munro' et "Capitaine Marsters" sonnaient plus courtoise, les enfants a persisté dans les surnoms, Colie et Cap'n Fred, ni de lesquels s’importaient de tout car les deux ont aimé les enfants.

En 1937, un service de bus a ouvert sur la rive et la Rotundus était vendu à William Campbell de Pembrooke qui lui converti en un remorqueur.

Pendant la seconde guerre mondiale, elle a servi comme un bateau de l’eau dans l’Halifax Harbour. Puis, revendu, elle a été envoyée à Sydney, Cap Breton avant la fin de la guerre, se dirigea vers une fois de plus le service de traversier.

Un peu plus loin des côtes du Cap-Breton, elle a rencontré dans le mauvais temps pour lequel elle n’était pas équipée et malheureusement elle a pataugé et a coulé. Le seul membre de son équipage ancien encore à bord était Cole Munro qui, au cours de cette nuit effrayante, a contribué à sauver des membres de l’équipage beaucoup plus jeunes que lui, puis tiré un aviron ainsi que d’autres survivants lorsqu’ils ont été forcés de prendre les canots de sauvetage. Cole, favori à tous ceux qui le connaissaient, est resté un membre de l’équipage Rotundus jusqu'à ce qu’elle a coulé.