The Hamburg

In the 1886, February 3rd edition of the ‘New York Maritime Register’ the ‘ship-building’ section announced that E. Churchill and Sons of Hantsport, Nova Scotia, planned to build a barque of 1700 tons. Many years later, Frederick William Wallace in his book “Wooden Ships and Iron Men” would give a mere paragraph to the largest wooden three-masted barque built in Canada – the ‘Hamburg’. The ‘W.D. Lawrence’, on the other hand, would write many pages in his book for being Canada’s largest wooden ship.

From her first trip to Liverpool to her last back home from New York in 1908 she was a busy and successful vessel. Almost without exception throughout this period her master was Andrew Beckworth Coldwell of Hantsport.

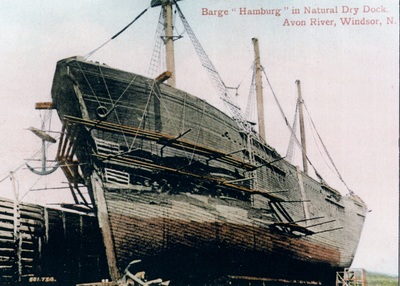

In 1908 she was bought by the J.B. king Company and converted into a gypsum barge at Hobart’s Wharf in Summerville. For the next 15 years she would be towed along with other old converted sailing vessels between here and New York.

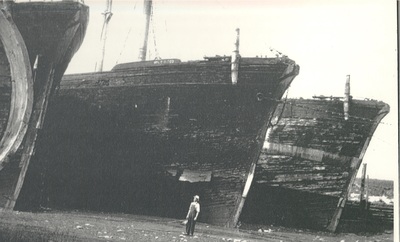

In 1925 the ‘Hamburg’ was layed beside the ‘Plymouth’, the ‘Wildwood’ and the ‘Ontario’ at Hobart’s Wharf. There, she gradually crumbled away with the other old vessels until in 1936 the Gypsum Company, fearing for people’s safety, decided to burn the old barges.

Today little can be seen of this vessel, for gradually silt has covered what is left of them. The exception is the port side of the ‘Hamburg’, which remains somewhat exposed. In this exhibit we take you back in time, from the ‘Hamburg’s’ remains as they exist today to her career as a great sailing vessel.

From her first trip to Liverpool to her last back home from New York in 1908 she was a busy and successful vessel. Almost without exception throughout this period her master was Andrew Beckworth Coldwell of Hantsport.

In 1908 she was bought by the J.B. king Company and converted into a gypsum barge at Hobart’s Wharf in Summerville. For the next 15 years she would be towed along with other old converted sailing vessels between here and New York.

In 1925 the ‘Hamburg’ was layed beside the ‘Plymouth’, the ‘Wildwood’ and the ‘Ontario’ at Hobart’s Wharf. There, she gradually crumbled away with the other old vessels until in 1936 the Gypsum Company, fearing for people’s safety, decided to burn the old barges.

Today little can be seen of this vessel, for gradually silt has covered what is left of them. The exception is the port side of the ‘Hamburg’, which remains somewhat exposed. In this exhibit we take you back in time, from the ‘Hamburg’s’ remains as they exist today to her career as a great sailing vessel.

On June 22 (year unknown, possibly 2003), armed with a provincial Shipwreck Survey Permit, we took measurements and photos of the ‘Hamburg’ with help from the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic. Pictured from left to right are: Marvin Moore (Curator of Marine History), David Walker (Naval Architect), Darrell Burke (Avon River Heritage Museum) and Derrick Harrison (Photographer). This photo was taken by Joey St. Clair Patterson.

One of the most puzzling features of the wreck is an extra layer of ceiling timbers found in the inner hull. These run longitudinally and are about 10” by 10”.

The photo of the wreck shows clearly that these ran from a flat deck built above the bilge to about three feet up the side. Certainly the first thing to suggest itself regarding the purpose for these, is for strengthening. It was also suggested that part of the purpose might be to take the punishment inflicted by dropping gypsum directly into the hold.

A letter in the book of Daniel Munroe the port captain for ‘J.B. King Co,’ dated December 14, 1912 states:

“… Capt. Lawrence is spending a lot of money on these barges and he is not spending according with my ideas to strengthen the vessel. I have had considerable experience myself in salt cargoes and none of us agree with Lawrence in raising the ‘Canada’s flooring any higher or putting more cargo in her tween decks, we must try to proportion it now about two-thirds in the lower hold and one third in the tween decks and that is all the weight that ought to go on her beams. The same is true of the ‘Hamburg’.”

We know from letter books in the Archives of the Fundy Gypsum Company that stevedores were used in the loading process. We can surmise that once the gypsum was dumped off the railcars and down the ramps into the hold that the stevedores moved the gypsum by hand in order to trim the vessel.

Once loaded the vessel would be taken out by a small tug to wait for the tow. The massive hawsers used for towing were manhandled by the barge crews. The hawsers were approximately 500 feet long and went from the aft towing bits off on to the bow of the next. Once under way the main concern was steering and trying to maintain as straight a line as possible. The small sails were used mainly when the wind was from the stern and they helped to push the barges along. The sails second purpose was an emergency propulsion in case a barge broke loose.

During her life as a barge, the ‘Hamburg’ made approximately 180 trips between Nova Scotia and the United States and carried an average of 2300 tons of plaster per trip. This means that over her life as a barge she carried around 414, 000.00 tons of gypsum.

The photo of the wreck shows clearly that these ran from a flat deck built above the bilge to about three feet up the side. Certainly the first thing to suggest itself regarding the purpose for these, is for strengthening. It was also suggested that part of the purpose might be to take the punishment inflicted by dropping gypsum directly into the hold.

A letter in the book of Daniel Munroe the port captain for ‘J.B. King Co,’ dated December 14, 1912 states:

“… Capt. Lawrence is spending a lot of money on these barges and he is not spending according with my ideas to strengthen the vessel. I have had considerable experience myself in salt cargoes and none of us agree with Lawrence in raising the ‘Canada’s flooring any higher or putting more cargo in her tween decks, we must try to proportion it now about two-thirds in the lower hold and one third in the tween decks and that is all the weight that ought to go on her beams. The same is true of the ‘Hamburg’.”

We know from letter books in the Archives of the Fundy Gypsum Company that stevedores were used in the loading process. We can surmise that once the gypsum was dumped off the railcars and down the ramps into the hold that the stevedores moved the gypsum by hand in order to trim the vessel.

Once loaded the vessel would be taken out by a small tug to wait for the tow. The massive hawsers used for towing were manhandled by the barge crews. The hawsers were approximately 500 feet long and went from the aft towing bits off on to the bow of the next. Once under way the main concern was steering and trying to maintain as straight a line as possible. The small sails were used mainly when the wind was from the stern and they helped to push the barges along. The sails second purpose was an emergency propulsion in case a barge broke loose.

During her life as a barge, the ‘Hamburg’ made approximately 180 trips between Nova Scotia and the United States and carried an average of 2300 tons of plaster per trip. This means that over her life as a barge she carried around 414, 000.00 tons of gypsum.

Experts from an interview with Archie Lake whose grandfather, Fulton Lake looked after the barges after they were beached at Summerville in 1925.

“I was down there when she came in [the ‘Hamburg’], my mother had me down there myself and my sister…everyone on the shore pretty near…I remember the ‘Mumford’ and the ‘Wack; [tugboats] had a hold of her.

“…to bad he wasn’t [alive – Archies brother Walter], he could tell you a lot more. He used to stay aboard the barges with grampy when grampy was tending them there. They stayed everynight down there. They had food on them and everything- the old ‘Hamburg’ did… the cockroachs- my God!’’

“Grandfather, he’d get his winter’s wood off em for years and years … deck plank was as solid as could be … they got to be dangerous.”

“Those big heavy chains, there was one fastened up to the big elm tree, they ‘fastened’ the ‘Hamburg’ there … she still floated her rear end would float up … how the hell they got that chain up there I don’t know”

“My father used to caulk on them (barges) my aunt when she was a little girl used to carry his lunch down to him at dinner time”

“I spent a lot of good times down there.”

“I was down there when she came in [the ‘Hamburg’], my mother had me down there myself and my sister…everyone on the shore pretty near…I remember the ‘Mumford’ and the ‘Wack; [tugboats] had a hold of her.

“…to bad he wasn’t [alive – Archies brother Walter], he could tell you a lot more. He used to stay aboard the barges with grampy when grampy was tending them there. They stayed everynight down there. They had food on them and everything- the old ‘Hamburg’ did… the cockroachs- my God!’’

“Grandfather, he’d get his winter’s wood off em for years and years … deck plank was as solid as could be … they got to be dangerous.”

“Those big heavy chains, there was one fastened up to the big elm tree, they ‘fastened’ the ‘Hamburg’ there … she still floated her rear end would float up … how the hell they got that chain up there I don’t know”

“My father used to caulk on them (barges) my aunt when she was a little girl used to carry his lunch down to him at dinner time”

“I spent a lot of good times down there.”

We are fortunate to have the crew agreement provided by Memorial University for the vessels arrival in Hamburg. The three officers were Andrew Coldwell; R.G. Churchill from Yarmouth as Mate and Frank Mosher from Summerville as Bosun. If this photo is from 1895 we know the identity of at least these people. The man with the cooks hat (second from the left would be Joseph Mercura from Montreal). Photo courtesy of the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic).

Summerville

I didn’t know the village when

The ships were being built

I didn’t see the quarry when they took the stone from it

I didn’t see the shipyards with the big ships and dry,

Their yards arms swinging sixty feet

From spars a hundred high.

The first that I remember

Were the barges lying there.

Their big black hulls seemed sulking

‘Neath their masts so ghostly bare.

And as we walked the decks of these

Great Clippers of their age

It seemed that history opened up-

Then someone turned the page.

Some thirty years before my time

This village thrived they say.

And Oh, the tales the oldsters tell,

Of men who caulked all day.

These once proud men of Summerville,

And oh it’s sad to know

That these great wharves will be no more

Nor big ships come and go.

I didn’t know the village when

The ships were being built

I didn’t see the quarry when they took the stone from it

I didn’t see the shipyards with the big ships and dry,

Their yards arms swinging sixty feet

From spars a hundred high.

The first that I remember

Were the barges lying there.

Their big black hulls seemed sulking

‘Neath their masts so ghostly bare.

And as we walked the decks of these

Great Clippers of their age

It seemed that history opened up-

Then someone turned the page.

Some thirty years before my time

This village thrived they say.

And Oh, the tales the oldsters tell,

Of men who caulked all day.

These once proud men of Summerville,

And oh it’s sad to know

That these great wharves will be no more

Nor big ships come and go.

En 1886, février 3eme édition de le « New York Maritime Register » la section « construction navale » a annoncé qu’E. Churchill et fils d’Hantsport, Nouvelle-Écosse, a prévu de construire un barque de 1700 tonnes. Plusieurs années plus tard, Frederick William Wallace dans son livre « Wooden Ships and Iron Men » donnerait un simple paragraphe pour la plus grande barque en bois avec trois mâts construite au Canada – le « Hamburg ». Le « W.D. Lawrence », par contre, écrira de nombreuses pages dans son livre pour être le plus grand navire en bois du Canada.

De son premier voyage à Liverpool à son dernier retour de New York en 1908 elle était un vaisseau occupé et brillant. Presque sans exception tout au long de cette période, son maître était Andrew Beckworth Coldwell de Hantsport.

En 1908, elle était achetée par la compagnie du J.B. King Company et convertie en une barge de gypse au quai de Hobart en Summerville. Pour les prochaines 15 années, elle serait être remorquée avec autres vieux vaisseaux converti entre ici et New York.

En 1925, le « Hamburg » est mis à côté du « Plymouth », le « Wildwood » et la « Ontario » au quai de Hobart. Là, elle a progressivement émietté avec les autres navires anciens jusqu’en 1936 la Compagnie du Gypse, craignant pour la sécurité des personnes, a décidé de brûler les vieilles barges.

Aujourd'hui peu sont visibles de ce navire, pour progressivement ce qui reste d’eux était couvert en sable. L’exception est le côté bâbord de la « Hamburg », qui reste un peu exposé. Dans cette exposition nous vous remontons dans le temps, des restes de la « Hamburg » tels qu’ils existent aujourd'hui à sa carrière d’un grand bateau à voile.

Le 22 juin, munis d’un permis de sondage de naufrage provincial, nous avons pris des mesures et des photos de la « Hamburg » avec l’aide du Musée Maritime de l’Atlantique. Sur la photo de gauche à droite : Marvin Moore (Conservateur de l’Histoire Maritime), David Walker (Architecte Naval), Darrell Burke (Avon River Heritage Museum) et Derrick Harrison (Photographe). Cette photo a été prise par Joey St. Clair Patterson.

Une des caractéristiques les plus déconcertants de l’épave est une couche supplémentaire de bois de plafond trouvés dans la coque intérieure. Ils sont en longitude et sont environ 10" par 10". La photo de l’épave montre clairement qu’il partait de plat-pont construit au-dessus de la cale d’environ trois pieds sur le côté. La première chose à suggérer lui-même de la finalité pour ces derniers, est certainement à renforcer. Il a également été suggéré que parti de l’objectif peut être de prendre la peine infligée en laissant tomber le plâtre directement dans la cale. Une lettre dans le livre de Daniel Munroe le capitaine du port pour « J.B. King Co, » en date du 14 décembre 1912 indique:

« … Le capitaine Lawrence dépensant beaucoup d’argent sur ces barges et il ne dépense pas selon mes idées pour renforcer le navire. J’ai eu beaucoup d’expérience moi-même dans des cargaisons de sels et aucun d'entre nous ne suis d’accord avec Laurence en remontant le plancher de Canada plus haut ou mettant plus de fret dans ses ponts d’entre, nous devons essayer de lui proportion maintenant environ deux-tiers dans la cale inférieure et un tiers dans les ponts d’entre et ça c’est tout le poids qui devrait aller sur ses poutres. Le même est vrai de la « Hamburg ». »

Nous savons des livres de lettres dans les Archives de la Fundy Gypsum Company, que les acconiers ont été utilisés dans le processus de chargement. Nous pouvons supposer qu’une fois le gypse a été jeté hors des autorails et vers le bas des rampes dans la cale que les acconiers s’installaient le gypse à la main afin de tailler le navire.

Une fois chargé, le navire soit pris par un petit remorqueur à attendre pour le remorquage. Les aussières massives utilisées pour le remorquage, ont été tenir par les équipages de la barge. Les aussières étaient environ 500 pieds de longueur et est passée des bits de remorquage arrière la poupe de la proue de l’autre. Une fois en cours la principale préoccupation était conduisant et essayant de maintenir en ligne droite la plus que possible. Les petites voiles servaient principalement lorsque le vent était de la poupe et ils ont contribué à pousser les barges le long. Le second objectif des voiles était une propulsion d’urgence dans le cas où une barge s’est déchaînée.

Au cours de sa vie comme une barge, la « Hamburg » fait environ 180 voyages entre la Nouvelle-Écosse et les États-Unis et a transporté une moyenne de 2300 tonnes de plâtre par voyage. Cela signifie qu’au cours de sa vie comme une barge, qu'elle a transporté environ 414 000,00 tonnes de gypse.

De son premier voyage à Liverpool à son dernier retour de New York en 1908 elle était un vaisseau occupé et brillant. Presque sans exception tout au long de cette période, son maître était Andrew Beckworth Coldwell de Hantsport.

En 1908, elle était achetée par la compagnie du J.B. King Company et convertie en une barge de gypse au quai de Hobart en Summerville. Pour les prochaines 15 années, elle serait être remorquée avec autres vieux vaisseaux converti entre ici et New York.

En 1925, le « Hamburg » est mis à côté du « Plymouth », le « Wildwood » et la « Ontario » au quai de Hobart. Là, elle a progressivement émietté avec les autres navires anciens jusqu’en 1936 la Compagnie du Gypse, craignant pour la sécurité des personnes, a décidé de brûler les vieilles barges.

Aujourd'hui peu sont visibles de ce navire, pour progressivement ce qui reste d’eux était couvert en sable. L’exception est le côté bâbord de la « Hamburg », qui reste un peu exposé. Dans cette exposition nous vous remontons dans le temps, des restes de la « Hamburg » tels qu’ils existent aujourd'hui à sa carrière d’un grand bateau à voile.

Le 22 juin, munis d’un permis de sondage de naufrage provincial, nous avons pris des mesures et des photos de la « Hamburg » avec l’aide du Musée Maritime de l’Atlantique. Sur la photo de gauche à droite : Marvin Moore (Conservateur de l’Histoire Maritime), David Walker (Architecte Naval), Darrell Burke (Avon River Heritage Museum) et Derrick Harrison (Photographe). Cette photo a été prise par Joey St. Clair Patterson.

Une des caractéristiques les plus déconcertants de l’épave est une couche supplémentaire de bois de plafond trouvés dans la coque intérieure. Ils sont en longitude et sont environ 10" par 10". La photo de l’épave montre clairement qu’il partait de plat-pont construit au-dessus de la cale d’environ trois pieds sur le côté. La première chose à suggérer lui-même de la finalité pour ces derniers, est certainement à renforcer. Il a également été suggéré que parti de l’objectif peut être de prendre la peine infligée en laissant tomber le plâtre directement dans la cale. Une lettre dans le livre de Daniel Munroe le capitaine du port pour « J.B. King Co, » en date du 14 décembre 1912 indique:

« … Le capitaine Lawrence dépensant beaucoup d’argent sur ces barges et il ne dépense pas selon mes idées pour renforcer le navire. J’ai eu beaucoup d’expérience moi-même dans des cargaisons de sels et aucun d'entre nous ne suis d’accord avec Laurence en remontant le plancher de Canada plus haut ou mettant plus de fret dans ses ponts d’entre, nous devons essayer de lui proportion maintenant environ deux-tiers dans la cale inférieure et un tiers dans les ponts d’entre et ça c’est tout le poids qui devrait aller sur ses poutres. Le même est vrai de la « Hamburg ». »

Nous savons des livres de lettres dans les Archives de la Fundy Gypsum Company, que les acconiers ont été utilisés dans le processus de chargement. Nous pouvons supposer qu’une fois le gypse a été jeté hors des autorails et vers le bas des rampes dans la cale que les acconiers s’installaient le gypse à la main afin de tailler le navire.

Une fois chargé, le navire soit pris par un petit remorqueur à attendre pour le remorquage. Les aussières massives utilisées pour le remorquage, ont été tenir par les équipages de la barge. Les aussières étaient environ 500 pieds de longueur et est passée des bits de remorquage arrière la poupe de la proue de l’autre. Une fois en cours la principale préoccupation était conduisant et essayant de maintenir en ligne droite la plus que possible. Les petites voiles servaient principalement lorsque le vent était de la poupe et ils ont contribué à pousser les barges le long. Le second objectif des voiles était une propulsion d’urgence dans le cas où une barge s’est déchaînée.

Au cours de sa vie comme une barge, la « Hamburg » fait environ 180 voyages entre la Nouvelle-Écosse et les États-Unis et a transporté une moyenne de 2300 tonnes de plâtre par voyage. Cela signifie qu’au cours de sa vie comme une barge, qu'elle a transporté environ 414 000,00 tonnes de gypse.