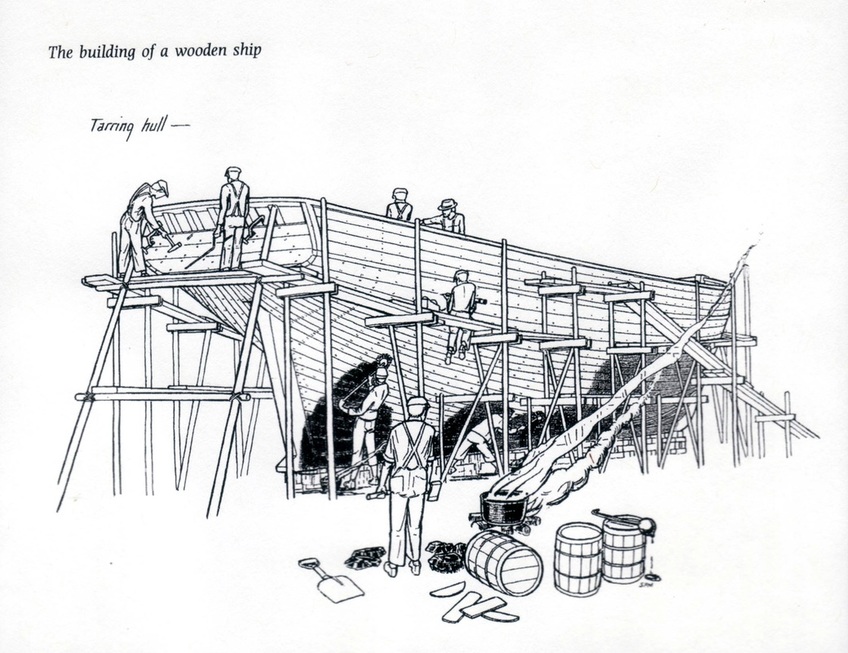

Shipbuilding Process

A yard producing major vessels, like the ones in Newport, was not just a cleared space where a group of men with hand tools threw a ship together. It was an organized, efficient factory often with a mill, saw pits, steam engine, blacksmith shop, joiners shop, moulding loft, timber booms, and the facilities needed to house and feed a hundred or more men.

There were no plans or blueprints. The master-builder would work from a small wooden model called a half-hull. This contained all the information he needed to supervise the construction of the hull. On the floor of the moulding loft he would use chalk to enlarge the various parts of the hull as needed, keel, frames, planking and so on.

Timber would be cut inland. In Newport, the logs were rafted down the Kennetcook and St. Croix Rivers. The mill at Newport had pipelines bringing water underground from a small pond (this mill burnt down in 1884). In Maritime ships the keel was generally made from White Oak as were the frames (although sometimes Eastern White Larch or as it was locally called Juniper, was sometimes used), and the hull planks were generally made from spruce or pine. Masts were constructed from pine or fir.

The ship was built outside on a crib work as close to the water as possible and the vessel would be launched on a spring tide.

The keel was built (or laid) on blocks and then the stem and sternposts attached. The frames or ribs were then built and bolted to the keel. Where the ribs were attached to the keel, was capped by a long, heavy beam called a keelson.

Then the eternal frames that would form the cargo space, cabins, decks and internal support were built. Now there was a skeleton ready to receive its skin – the planking.

All of this wood was cut as close to the required shape as possible, but a ship is not a house. It has complicated curves and the skilful use of tools like broad axes, adzes and steam boxes to shape and coal wood into the required forms was essential. All were fastened together by copper and iron bolts and wooden dowels called trunnels (from: tree-nail).

All the seams then had to be sealed and made water-tight and this was done by pounding picked apart rope fibres (oakum) permeated with pitch (derived from pine tar). The process was called caulking and the man who did it, a caulker.

The vessel was now ready for finishing work, the addition of carpentry details and operating systems like rudder and wheel and iron work. When the masts were put in this was called stepping the mast. The rigging was the rope, wire and chain used to stabilize the masts and operate the sails.

Depending on the size of the yard the rigging might be contracted to a rigger off site or done in house. The same was true of the sails, though most often this was done by a specialist, in a sail loft (we know of at least one that existed in Windsor). As you can see, building a ship was a complicated endeavour that called for a high degree of organization and the bringing together of a tremendous amount of skills.

Once the ship has been framed and decks planed off to a smooth cambered surface, and the planking finished on the outside with planes and adzes. Then she would be ready for caulking, that is, sealing the seams between the planks (still spoken of as ‘seams’ a thousand years after they had ceased to be sewn) with oakum – hemp fibre held in position with tar on the outside. Caulking was an extremely important process, not only because by squeezing the planks together tightly and holding them in tension once it was wet and had expanded, it added to the rigidity and strength of the vessel. During caulking it was very important to allow for expansion of the planks then wetted. If you did not serious damage could occur. Tom Perkins pictures the caulking process vividly:

Outside, the planking was faired by hand planning to give a smooth finish to the seams, and caulking would begin. Caulking was a task of monotonous repetition. Shipwrights could always caulk, everyone had the gear necessary, but some yards employed wood-caulkers as a gang something like a sub-contract, and this led to a special breed of working, with plenty of stamina and an ability to overcome such a mundane task. Before work began, the pitch in black form was broken up by hammering and put into a cast metal pot of traditional shape with a large bow handle. Standing on a grid with a wood-and-shavings fire underneath, the pots would be dotted down the slipway local to each caulker’s workplace; ladles would be cleaned of the melting tar, the residue from the previous day’s work. Around the fires, squatting on box stools (which housed their mallet and irons) caulkers would be unpackaging oakum in long skeins from the hundredweight bales. Quickly and adeptly, the skein would be teased across the thigh (covered by canvas or a leather patch) and rolled a thread of uniform thickness forming a ball of manageable size. Stockholm tar [pinewood tar, obtained tradition from Finland and shipped through Stockholm until 1765, by which time and the name had become attached to it for ever] was the preservative used in oakum an it permeated even the skin with a dark brown staining. As soon as sufficient oakum for a morning was rolled, the caulker would start laying a thread into the garboard seam, and so on up to the turn of bilge, usually working a shift of about seven or eight planks (widthwise) so as to prevent the plank next to the first to be caulked tightening by undue final caulking was not gradual in its advance up the hull. Caulking the oakum was the job of the making-iron or caulking-iron driving it was the job of the mallet, and what a tool that was! Most mallets were handmade, starting with a 4 inch by 4 inch block of African oak or equivalent timber, such as best English oak or box wood, or even lignum vitae about 15 inches long.

Caulking was finished at the outside of the seam after ‘reeding’, and molten pitch was ‘rolled on’ by mops or brushes to fill the seam proud, scraped off when hardened leaving a watertight joint.

‘Paying up’ was the operation with the mops, and it was a messy job since ‘rolling in’, the art of putting pitch up ‘under’, covered the slipway and the caulker with pitch, especially in the summer. Pitch that fell across the back of the hand could be dissolved by benzene, but not before a gigantic blister, yellow in colour, had formed. Many caulkers had surface burns to the face and neck especially when the regular ‘payers up’ were sick or away from work. Boots stuck to the floor; smoke was in abundance from the fires and boiling pitch. All the caulking mallets used at our Master’s shipyard had slots cut in each head, producing a clear ringing note when the mallet was used. There were two reasons for this, aesthetic and one practical. Since each mallet was cut a little differently, each produced an individual note and thus a whole succession of notes and combinations came from the slipway when caulking was going forward. The practical reason for the slots was that the dull thud of the mallet on the iron very close to the head for hour after would have been quite intolerable, indeed perhaps even dangerous, to the men employed in this work. So the mallet was cut to produce a pleasant sound in use and one which did not damage the ears of its user, even though he might swing the mallet for twelve hours a day for days on end. Nevertheless, many caulkers became deaf in their later years.

There were no plans or blueprints. The master-builder would work from a small wooden model called a half-hull. This contained all the information he needed to supervise the construction of the hull. On the floor of the moulding loft he would use chalk to enlarge the various parts of the hull as needed, keel, frames, planking and so on.

Timber would be cut inland. In Newport, the logs were rafted down the Kennetcook and St. Croix Rivers. The mill at Newport had pipelines bringing water underground from a small pond (this mill burnt down in 1884). In Maritime ships the keel was generally made from White Oak as were the frames (although sometimes Eastern White Larch or as it was locally called Juniper, was sometimes used), and the hull planks were generally made from spruce or pine. Masts were constructed from pine or fir.

The ship was built outside on a crib work as close to the water as possible and the vessel would be launched on a spring tide.

The keel was built (or laid) on blocks and then the stem and sternposts attached. The frames or ribs were then built and bolted to the keel. Where the ribs were attached to the keel, was capped by a long, heavy beam called a keelson.

Then the eternal frames that would form the cargo space, cabins, decks and internal support were built. Now there was a skeleton ready to receive its skin – the planking.

All of this wood was cut as close to the required shape as possible, but a ship is not a house. It has complicated curves and the skilful use of tools like broad axes, adzes and steam boxes to shape and coal wood into the required forms was essential. All were fastened together by copper and iron bolts and wooden dowels called trunnels (from: tree-nail).

All the seams then had to be sealed and made water-tight and this was done by pounding picked apart rope fibres (oakum) permeated with pitch (derived from pine tar). The process was called caulking and the man who did it, a caulker.

The vessel was now ready for finishing work, the addition of carpentry details and operating systems like rudder and wheel and iron work. When the masts were put in this was called stepping the mast. The rigging was the rope, wire and chain used to stabilize the masts and operate the sails.

Depending on the size of the yard the rigging might be contracted to a rigger off site or done in house. The same was true of the sails, though most often this was done by a specialist, in a sail loft (we know of at least one that existed in Windsor). As you can see, building a ship was a complicated endeavour that called for a high degree of organization and the bringing together of a tremendous amount of skills.

Once the ship has been framed and decks planed off to a smooth cambered surface, and the planking finished on the outside with planes and adzes. Then she would be ready for caulking, that is, sealing the seams between the planks (still spoken of as ‘seams’ a thousand years after they had ceased to be sewn) with oakum – hemp fibre held in position with tar on the outside. Caulking was an extremely important process, not only because by squeezing the planks together tightly and holding them in tension once it was wet and had expanded, it added to the rigidity and strength of the vessel. During caulking it was very important to allow for expansion of the planks then wetted. If you did not serious damage could occur. Tom Perkins pictures the caulking process vividly:

Outside, the planking was faired by hand planning to give a smooth finish to the seams, and caulking would begin. Caulking was a task of monotonous repetition. Shipwrights could always caulk, everyone had the gear necessary, but some yards employed wood-caulkers as a gang something like a sub-contract, and this led to a special breed of working, with plenty of stamina and an ability to overcome such a mundane task. Before work began, the pitch in black form was broken up by hammering and put into a cast metal pot of traditional shape with a large bow handle. Standing on a grid with a wood-and-shavings fire underneath, the pots would be dotted down the slipway local to each caulker’s workplace; ladles would be cleaned of the melting tar, the residue from the previous day’s work. Around the fires, squatting on box stools (which housed their mallet and irons) caulkers would be unpackaging oakum in long skeins from the hundredweight bales. Quickly and adeptly, the skein would be teased across the thigh (covered by canvas or a leather patch) and rolled a thread of uniform thickness forming a ball of manageable size. Stockholm tar [pinewood tar, obtained tradition from Finland and shipped through Stockholm until 1765, by which time and the name had become attached to it for ever] was the preservative used in oakum an it permeated even the skin with a dark brown staining. As soon as sufficient oakum for a morning was rolled, the caulker would start laying a thread into the garboard seam, and so on up to the turn of bilge, usually working a shift of about seven or eight planks (widthwise) so as to prevent the plank next to the first to be caulked tightening by undue final caulking was not gradual in its advance up the hull. Caulking the oakum was the job of the making-iron or caulking-iron driving it was the job of the mallet, and what a tool that was! Most mallets were handmade, starting with a 4 inch by 4 inch block of African oak or equivalent timber, such as best English oak or box wood, or even lignum vitae about 15 inches long.

Caulking was finished at the outside of the seam after ‘reeding’, and molten pitch was ‘rolled on’ by mops or brushes to fill the seam proud, scraped off when hardened leaving a watertight joint.

‘Paying up’ was the operation with the mops, and it was a messy job since ‘rolling in’, the art of putting pitch up ‘under’, covered the slipway and the caulker with pitch, especially in the summer. Pitch that fell across the back of the hand could be dissolved by benzene, but not before a gigantic blister, yellow in colour, had formed. Many caulkers had surface burns to the face and neck especially when the regular ‘payers up’ were sick or away from work. Boots stuck to the floor; smoke was in abundance from the fires and boiling pitch. All the caulking mallets used at our Master’s shipyard had slots cut in each head, producing a clear ringing note when the mallet was used. There were two reasons for this, aesthetic and one practical. Since each mallet was cut a little differently, each produced an individual note and thus a whole succession of notes and combinations came from the slipway when caulking was going forward. The practical reason for the slots was that the dull thud of the mallet on the iron very close to the head for hour after would have been quite intolerable, indeed perhaps even dangerous, to the men employed in this work. So the mallet was cut to produce a pleasant sound in use and one which did not damage the ears of its user, even though he might swing the mallet for twelve hours a day for days on end. Nevertheless, many caulkers became deaf in their later years.

La Construction Navale

Un fois que le navire a été encadré et les ponts ont été aplani à une surface lisse et incurvé, et le bordé était fini sur l’extérieur avec les rabots et herminettes. Ensuite elle aurait été prêt pour calfatant, ça c’est, rebouchant les coutures entre les planches (encore parlé comme « coutures » un mille d’ans après ils ont cessé d’être cousu) avec l’étoupe – fibre de chanvre tenait en position avec goudron sur l’extérieur. Calfatant était un processus extrêmement important, pas seulement parce-que par pressant les planches ensemble fermement et les tenant en tension une fois qu’ils étaient mouillé et avaient agrandi, il ajoutait à la rigidité et force du vaisseau. Pendant calfatant c’était très important de prenait en considération la dilatation des planches mouillé. Si non les dommages sérieux peuvent se passer. Tom Perkins imagine le processus de calfatant parfaitement:

Dehors, le bordé était par aplanant à la main pour donner une finition lisse aux coutures, et calfatant aurait commencé. Calfatant était un tache de répétition monotone. Les charpentiers de marine pouvaient toujours calfater, tout le monde avait le matériel nécessaire, mais quelques chantiers navals ont employé calfats-de-bois comme un équipe, quelque chose comme un contrat de sous-traitance, et ça a mené à une espèce spéciale de travail, avec une abondance d’endurance et une capacité de surmonter la tache banal. Avant le travail à commencer, le bitume en forme noir était fragmenté par enfonçant et mis dans un pot de moule en métal de forme traditionnelle avec un grand manche courbé. Sur une grille avec un feu de bois et copeaux dessous, les pots auraient été parsemés le long de la cale locale de chaque lieu de travail du calfat; les louches auraient été nettoyées du goudron fondant, le résidu du travail du jour auparavant. Autour des feux, accroupissant sur les boîtes-tabourets (qui ont hébergé leur maillet et fers) les calfats auraient pris l’étoupe en les écheveaux longs des balles de cent livres. Rapidement et en une manière experte, l’écheveau aurait détaché tout doucement à travers la cuisse (couvert avec la toile ou une pièce de cuir) et roulé un fil de épaisseur uniforme formant un balle de taille gérable. Le goudron de Stockholm (goudron en pin, tradition obtenu de la Finlande et expédié par Stockholm jusqu’à 1765, auquel temps que le nom avait devenu l’attaché pour toujours) était la conservateur utilisé dans l’étoupe et il s’est répandu, le calfat aurait commencé mettant un fil dans la couture garboard, et ainsi de suite jusqu’à la tourne de fond de cale, soudainement travaillant une équipe d’environ sept ou huit planches (en largueur) concernant le prévention de la planche à la côté de la première d’être calfaté de serré par la calfater finale excessive n’était pas progressive dans son avancée en haut de la coque. Calfatant l’étoupe était le travail du fer de calfatant, le heurtant était le travail du maillet, et quel outil il était! La plupart des maillets était fait à la main, commençant avec un 4 pouce par 4 pouces bloc de chêne africain ou le bois équivalente, meilleur chêne Anglais ou buis, ou même Gaïac environ 15 pouces en longueur.

Calfatant était fini au extérieur de la couture après « canissant », et le bitume fondu était « roulé sur » par les balais à franges ou brosses pour remplir la couture, gratté quand durci laissant une charnière étanche.

« Passant à la caisse » était l’opération avec les balais à franges, et c’était un travail sale car « roulant dans », l’art de mettant un bitume debout « sous », a couvert la cale et le calfat avec le bitume, particulièrement dans l’été. Le bitume qui est tombé sur la main pouvait être dissoudre par benzène, mais avant une énorme ampoule, jaune en couleur, avait formé. Plusieurs calfats avaient les brûlures de surface au visage et cou particulièrement quand les « Passeurs à la caisse » réguliers étaient malades ou parti de travail. Les bottes coincé au plancher; la fumée était en abondance des feux et le bitume brouillant. Tous les maillets de calfater utilisaient au capitaine de notre chantier navale avaient les fentes dans chaque tête, produisant une note clair qui sonne quand le maillet était utilisé. Il y avait deux raisons pour ceci, esthétique et une pratique. Car chaque maillet étaient coupé un petit peu diffèrent, chacun produisait une note individuel et ainsi une succession entière de notes et combinaisons venait de la cale quand la calfatant s’est passé. La raison pratique pour les fentes était que le bruit sourd du maillet sur le fer très proche à la tête au fil des heures aurait été assez intolérable, en effet peut-être même dangereux, aux hommes employé dans ce travail. Alors le maillet était coupé pour produire un son plaisant en utilisation et un qui n’endommager les oreilles de son utilisateur, bien qu’il pourrait balançait le maillet pour douze heures par jour pour des jours et des jours. Néanmoins, plusieurs calfats ont devient sourds dans leurs années plus tard.

Dehors, le bordé était par aplanant à la main pour donner une finition lisse aux coutures, et calfatant aurait commencé. Calfatant était un tache de répétition monotone. Les charpentiers de marine pouvaient toujours calfater, tout le monde avait le matériel nécessaire, mais quelques chantiers navals ont employé calfats-de-bois comme un équipe, quelque chose comme un contrat de sous-traitance, et ça a mené à une espèce spéciale de travail, avec une abondance d’endurance et une capacité de surmonter la tache banal. Avant le travail à commencer, le bitume en forme noir était fragmenté par enfonçant et mis dans un pot de moule en métal de forme traditionnelle avec un grand manche courbé. Sur une grille avec un feu de bois et copeaux dessous, les pots auraient été parsemés le long de la cale locale de chaque lieu de travail du calfat; les louches auraient été nettoyées du goudron fondant, le résidu du travail du jour auparavant. Autour des feux, accroupissant sur les boîtes-tabourets (qui ont hébergé leur maillet et fers) les calfats auraient pris l’étoupe en les écheveaux longs des balles de cent livres. Rapidement et en une manière experte, l’écheveau aurait détaché tout doucement à travers la cuisse (couvert avec la toile ou une pièce de cuir) et roulé un fil de épaisseur uniforme formant un balle de taille gérable. Le goudron de Stockholm (goudron en pin, tradition obtenu de la Finlande et expédié par Stockholm jusqu’à 1765, auquel temps que le nom avait devenu l’attaché pour toujours) était la conservateur utilisé dans l’étoupe et il s’est répandu, le calfat aurait commencé mettant un fil dans la couture garboard, et ainsi de suite jusqu’à la tourne de fond de cale, soudainement travaillant une équipe d’environ sept ou huit planches (en largueur) concernant le prévention de la planche à la côté de la première d’être calfaté de serré par la calfater finale excessive n’était pas progressive dans son avancée en haut de la coque. Calfatant l’étoupe était le travail du fer de calfatant, le heurtant était le travail du maillet, et quel outil il était! La plupart des maillets était fait à la main, commençant avec un 4 pouce par 4 pouces bloc de chêne africain ou le bois équivalente, meilleur chêne Anglais ou buis, ou même Gaïac environ 15 pouces en longueur.

Calfatant était fini au extérieur de la couture après « canissant », et le bitume fondu était « roulé sur » par les balais à franges ou brosses pour remplir la couture, gratté quand durci laissant une charnière étanche.

« Passant à la caisse » était l’opération avec les balais à franges, et c’était un travail sale car « roulant dans », l’art de mettant un bitume debout « sous », a couvert la cale et le calfat avec le bitume, particulièrement dans l’été. Le bitume qui est tombé sur la main pouvait être dissoudre par benzène, mais avant une énorme ampoule, jaune en couleur, avait formé. Plusieurs calfats avaient les brûlures de surface au visage et cou particulièrement quand les « Passeurs à la caisse » réguliers étaient malades ou parti de travail. Les bottes coincé au plancher; la fumée était en abondance des feux et le bitume brouillant. Tous les maillets de calfater utilisaient au capitaine de notre chantier navale avaient les fentes dans chaque tête, produisant une note clair qui sonne quand le maillet était utilisé. Il y avait deux raisons pour ceci, esthétique et une pratique. Car chaque maillet étaient coupé un petit peu diffèrent, chacun produisait une note individuel et ainsi une succession entière de notes et combinaisons venait de la cale quand la calfatant s’est passé. La raison pratique pour les fentes était que le bruit sourd du maillet sur le fer très proche à la tête au fil des heures aurait été assez intolérable, en effet peut-être même dangereux, aux hommes employé dans ce travail. Alors le maillet était coupé pour produire un son plaisant en utilisation et un qui n’endommager les oreilles de son utilisateur, bien qu’il pourrait balançait le maillet pour douze heures par jour pour des jours et des jours. Néanmoins, plusieurs calfats ont devient sourds dans leurs années plus tard.