Avon Peninsula Watershed Preservation Society, circa 2006

We talk to local ecology advocate Raymond Parker about his involvement in the struggle against Fundy Gypsum Company to keep strip-mines from expanding into the heart of the Avon Peninsula, and the founding of the Avon Peninsula Watershed Preservation Society (APWPS).

Transcription of Interview with Raymond Parker, Wednesday, July 7th, 2021

Raymond Parker: Well, as you were just mentioning about the museum's interest in the APWPS and having a page and revitalizing the society, and what documents might be available from the old days when the society came to be. Well, that's cool because in the last few days when I was thinking about this, and frankly, it was so long ago that it's all a bit of a blur for me. But I did manage to find a USB drive, which has a lot of our documentation, including our main document, which we have a copy of here at the Museum. (Avon Peninsula Watershed Society, Comments on CGC Inc.’s Focus Report, 23 November 2009). So that's great.

Tacha Reed: Okay, good.

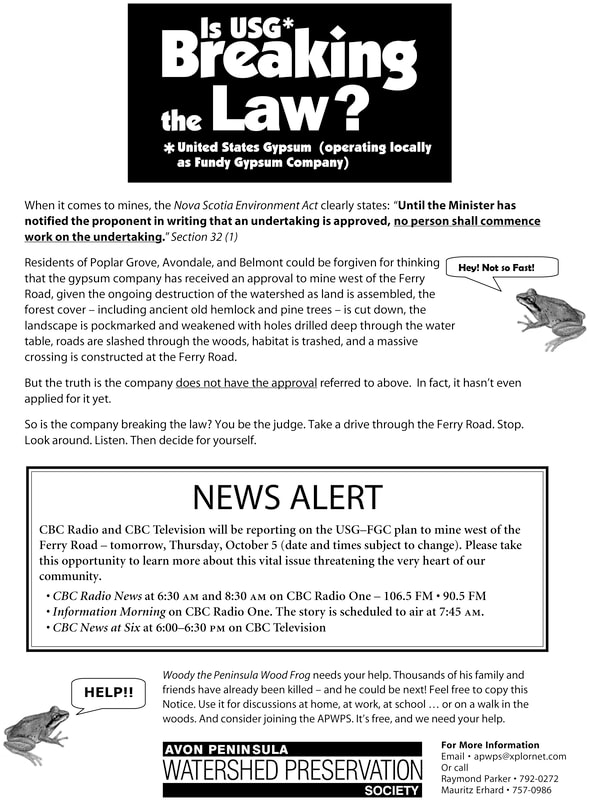

R: In fact, as I was going over this I think, for the community, the proposal for a new strip-mine, or a greatly expanded strip-mine in the watershed, it was full on for four years from the time they (the gypsum company) announced their proposal for what they were going to do. Though they didn't get into the details, we had to dig that out, but that was I think in the fall of 2005. Then there were a couple of environmental assessments, which we were very much involved in. Then the last decision by the Department of Environment was in the fall of 2009 where they did approve the proposal, but they had a couple of pages of fairly stringent conditions on the proposal. Which we felt, well, if we could actually have eyes on the ground to make sure that those conditions were adhered to, there's no way that they could actually mine there.

T: And that was about protecting the endangered species?

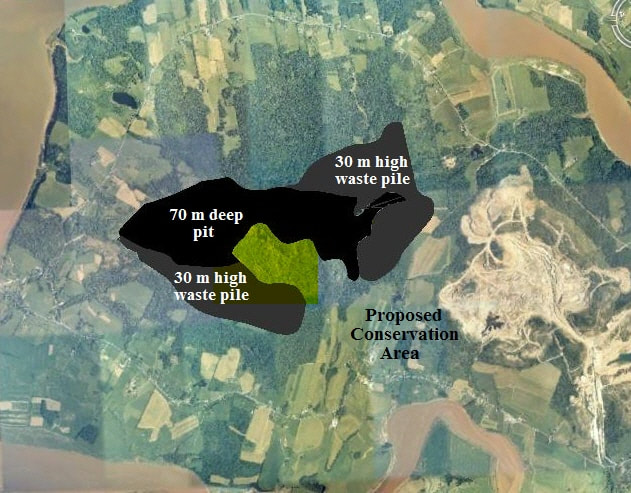

R: Well, that was just one of many, many, issues that basically strip-mining the interior of the peninsula would have caused. Somehow we got wind- I guess the mine started to have a few, I forget what they called them, small community meetings that were basically a dog and pony show where they were extolling the virtues of the proposed "expansion” as they called it. And, actually, at that time, somehow Ken Greer had got an invitation to actually go to the mine's environmental consultant’s office and look at more of what they were talking about and he invited me along. So we went down there and met with the consultant. Just sort of flipping through some of the material, you know? We saw a map and it was just... I'll describe later, how big a mine this was going to be, but it was huge and deep and right in the middle of our watershed. So, Ken and I left and I'm in the parking lot. We looked at each other and said, “this cannot happen”. "There's no way this is going to happen to our community."

Tacha Reed: Okay, good.

R: In fact, as I was going over this I think, for the community, the proposal for a new strip-mine, or a greatly expanded strip-mine in the watershed, it was full on for four years from the time they (the gypsum company) announced their proposal for what they were going to do. Though they didn't get into the details, we had to dig that out, but that was I think in the fall of 2005. Then there were a couple of environmental assessments, which we were very much involved in. Then the last decision by the Department of Environment was in the fall of 2009 where they did approve the proposal, but they had a couple of pages of fairly stringent conditions on the proposal. Which we felt, well, if we could actually have eyes on the ground to make sure that those conditions were adhered to, there's no way that they could actually mine there.

T: And that was about protecting the endangered species?

R: Well, that was just one of many, many, issues that basically strip-mining the interior of the peninsula would have caused. Somehow we got wind- I guess the mine started to have a few, I forget what they called them, small community meetings that were basically a dog and pony show where they were extolling the virtues of the proposed "expansion” as they called it. And, actually, at that time, somehow Ken Greer had got an invitation to actually go to the mine's environmental consultant’s office and look at more of what they were talking about and he invited me along. So we went down there and met with the consultant. Just sort of flipping through some of the material, you know? We saw a map and it was just... I'll describe later, how big a mine this was going to be, but it was huge and deep and right in the middle of our watershed. So, Ken and I left and I'm in the parking lot. We looked at each other and said, “this cannot happen”. "There's no way this is going to happen to our community."

So from that, the ball started rolling on our side. And community member Keith Hare organized a series of meetings in the Belmont Community Hall over, I think probably, over the winter of 2006. Those were very well attended. The Hall was packed, even more packed than during the community breakfasts they used to have there. We had, you know, municipal counsellors and maybe even provincial and federal representatives that attended. Very lively, very intense. And you know “what, what was the community's position on this”? And of course, there's a lot of back and forth. Keith eventually organized a secret ballot, “Yay” or “Nay”, on whether the community was in favour of the mine's proposal. I think at the time Keith didn't reveal the exact results publicly. According to some documentation I was looking at last night it looks like maybe it was 87% "Nay", if that's where that statistic came from, I can't be sure of that. But anyway, we were told by the various political representatives, “you need to get yourselves organized and form an organization to represent the community's position here”. And so in the spring of 2006, a smaller group of us got together and incorporated the Avon Peninsula Watershed Preservation Society (APWPS). And then we had our first big public meeting.

T: Okay.

R: And by the way, when in the process of forming the society, in the first place, you know, we hashed out our mission statement and our vision, goals, and objectives, which I’m happy to find we have here. And they're really pretty cool and stand up well all these years later.

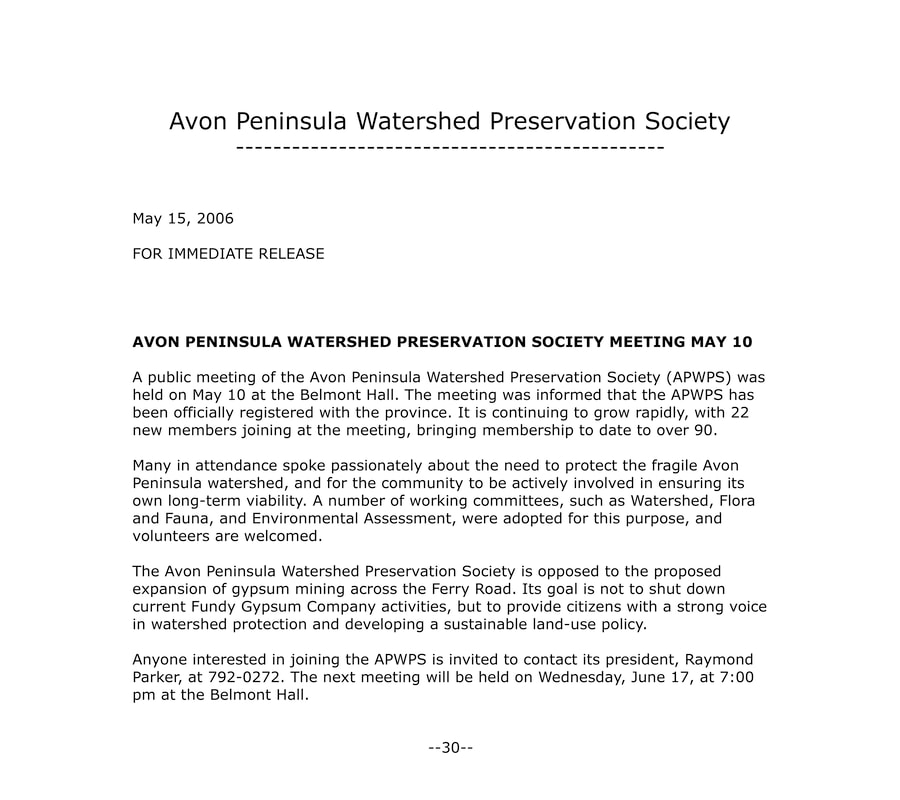

T: So I looked it up, the society was first incorporated or registered in May of 2006.

R: So okay: (reading from notes) Fall 2005, mine announces its proposed expansion; Winter 2006, Keith holds the series of town hall meetings; Spring 2006, APWPS formed with its Mission, Vision and so on; May 10, 2006, we have our first public meeting; and then a larger one on the 17th of June. Which, as it turns out, was 15 years ago last June. As our communications guy, Moe Erhard wrote in our press release for that meeting, something like, “the APWPS hit the ground running, for a well attended public meeting with 15 board members and nine committees".

T: Okay.

R: And by the way, when in the process of forming the society, in the first place, you know, we hashed out our mission statement and our vision, goals, and objectives, which I’m happy to find we have here. And they're really pretty cool and stand up well all these years later.

T: So I looked it up, the society was first incorporated or registered in May of 2006.

R: So okay: (reading from notes) Fall 2005, mine announces its proposed expansion; Winter 2006, Keith holds the series of town hall meetings; Spring 2006, APWPS formed with its Mission, Vision and so on; May 10, 2006, we have our first public meeting; and then a larger one on the 17th of June. Which, as it turns out, was 15 years ago last June. As our communications guy, Moe Erhard wrote in our press release for that meeting, something like, “the APWPS hit the ground running, for a well attended public meeting with 15 board members and nine committees".

In the spring of 2006, we managed to form and register the APWPS with the Province as a Society. As I say, we had a very large board of 15, and we had numerous committees, each with a chair. And we hit the ground running, as Moe said. And then, just to complete that timeline and skip a whole lot of community activity in between, in February of 2007, the Gypsum Company registered its proposal with the Department of Environment. So that's the first official stage with respect to the mine's relation to the Province. Though, obviously they've been working behind the scenes for years, probably in fact decades, with various government entities. You know, preparing the way for this proposal.

So that was in February. The registration document was an inch or two thick so it took a while to get through it, and as we only had 30 days to respond with our comments it was quite a rush, but we submitted our comments and so did many other individuals and organizations as well. Then in March, Mark Parent, who was the Minister of Environment for the Province at the time, asked for more information from the company, also known as a Focus Report, and gave the company another year to come up with that.

Then in October, I think probably October 2009 the mine submitted its Focus Report. Again, we only had 30 days to read, assimilate, and make our comments on the report, which was another thick document of several hundred pages. And so we did that. And actually it was fortunate, Matt Smith had come into the community some time before that and he was really good with some of the scientific details of our assessment, specifically with respect to the plants and animals and the streams and wetlands.

Anyway, we submitted our comments on the company's focus report, (displays documents) and then sometime later the minister released the decision that approved the project, but with some fairly stringent conditions. By the way I believe the Museum has a copy of the comments coming from the general public, other non-governmental organizations as well as the relevant departments from various levels of government. So that was four years--four very intense years and just hundreds and hundreds of hours of community volunteer time. And that's the story as brief as I can make it.

Anyway, we submitted our comments on the company's focus report, (displays documents) and then sometime later the minister released the decision that approved the project, but with some fairly stringent conditions. By the way I believe the Museum has a copy of the comments coming from the general public, other non-governmental organizations as well as the relevant departments from various levels of government. So that was four years--four very intense years and just hundreds and hundreds of hours of community volunteer time. And that's the story as brief as I can make it.

T: So I noticed when I was going through the registry of joint stock, you seem to have had a bit of a resurgence In 2015. I noticed that at that point, Gillian Robinson, Megan Dickinson, Aaron Spares, Magda Percy, Rob Bowkett, and Ross McFarland all joined as directors. So, I was curious, was there something that happened that brought new interest or you were just in the right place at the right time?

R: Well that's a good question. Basically, I think after the decision was handed down, we were all pretty much exhausted, like really, and, you know, this kind of crisis motivation wasn't there to drive us all forward in that respect. And the president, who remained to be me, was distracted by different things. So it was... we didn't manage to keep up with regular meetings and missed AGMs as well. So that one in 2015 was one we managed to have, and frankly, I hope that wasn't the last one, but it might have been.

T: I think it was. (crosstalk) The society defaulted in May of 2015. So...

R: Okay, so yeah, on and on, years pass by, that's kind of where we're at now, right? I have to say, in looking through this, you know, this saga of the community struggle with this proposed strip-mining. It's really quite a story; and it would be, you know, if someone who was interested, you know, a historian, you know, maybe some graduate student, political scientist or, you know, someone along those lines. There's lots of soil there to till, so to speak. And it would be, it would be good to have it, you know, that, that story told not just for historical interest’s sake, but also heaven forbid that particular situation raises its head again. Which it can at any moment because the land is still owned by a huge global mining corporation as far as we know, headquartered still in Chicago.

Then it would be good to have the record there about the various things that we did and we developed. And just a lot of knowledge. Not only about our peninsula and the watershed and how it works, how the hydrology works and about the flora and fauna, the animals and plants. But also how the Municipal, Provincial, and Federal entities that ultimately, you know, decide our fate. How those all work, particularly when it comes to mining policy.

In fact, one of the appendices in our comments on the Focus Report in 2009 is a... I don't know, it's 20 pages or something, but a paper that I was commissioned by the Sierra Club and the Ecology Action Centre on mining policy in the province and how that, you know, kind of regulatory framework for mining, which basically is there to allow mining to happen. That's what it does, right? With some regulations here and there. So yeah, I think that kind of says where we're at at the moment. (APWPS, Toward a Mineral Strategy for the New Nova Scotia: From Mitigation to Sustainability.)

R: Well that's a good question. Basically, I think after the decision was handed down, we were all pretty much exhausted, like really, and, you know, this kind of crisis motivation wasn't there to drive us all forward in that respect. And the president, who remained to be me, was distracted by different things. So it was... we didn't manage to keep up with regular meetings and missed AGMs as well. So that one in 2015 was one we managed to have, and frankly, I hope that wasn't the last one, but it might have been.

T: I think it was. (crosstalk) The society defaulted in May of 2015. So...

R: Okay, so yeah, on and on, years pass by, that's kind of where we're at now, right? I have to say, in looking through this, you know, this saga of the community struggle with this proposed strip-mining. It's really quite a story; and it would be, you know, if someone who was interested, you know, a historian, you know, maybe some graduate student, political scientist or, you know, someone along those lines. There's lots of soil there to till, so to speak. And it would be, it would be good to have it, you know, that, that story told not just for historical interest’s sake, but also heaven forbid that particular situation raises its head again. Which it can at any moment because the land is still owned by a huge global mining corporation as far as we know, headquartered still in Chicago.

Then it would be good to have the record there about the various things that we did and we developed. And just a lot of knowledge. Not only about our peninsula and the watershed and how it works, how the hydrology works and about the flora and fauna, the animals and plants. But also how the Municipal, Provincial, and Federal entities that ultimately, you know, decide our fate. How those all work, particularly when it comes to mining policy.

In fact, one of the appendices in our comments on the Focus Report in 2009 is a... I don't know, it's 20 pages or something, but a paper that I was commissioned by the Sierra Club and the Ecology Action Centre on mining policy in the province and how that, you know, kind of regulatory framework for mining, which basically is there to allow mining to happen. That's what it does, right? With some regulations here and there. So yeah, I think that kind of says where we're at at the moment. (APWPS, Toward a Mineral Strategy for the New Nova Scotia: From Mitigation to Sustainability.)

T: So, do you think it's worthwhile trying to recruit people and revitalize the society again?

R: Well... I do! And the thing is, when... maybe I'll read some of this Mission\Vision material. But there, it's like, wow, this is an awesome place with awesome people and most of us, you know, we love it. And there's always ongoing issues. You know, love it or lose it, really.

As we see with the ongoing kerfuffle with the causeway, just up the river, and if we had anything like the organization that we had in those early years, then that is a pretty powerful voice about what gets to happen and what doesn't. If we were able to raise that up again then we could have a real impact around issues like the (Windsor) causeway. And whatever else comes up, or similar issues.

R: Well... I do! And the thing is, when... maybe I'll read some of this Mission\Vision material. But there, it's like, wow, this is an awesome place with awesome people and most of us, you know, we love it. And there's always ongoing issues. You know, love it or lose it, really.

As we see with the ongoing kerfuffle with the causeway, just up the river, and if we had anything like the organization that we had in those early years, then that is a pretty powerful voice about what gets to happen and what doesn't. If we were able to raise that up again then we could have a real impact around issues like the (Windsor) causeway. And whatever else comes up, or similar issues.

The Flora + Fauna of the Avon Peninsula, captured by Wayne Young on the Westbrook Trail, June, 2020

T: I remember, I don’t know if it was something I watched or I read, but it was talking about what we now call the Wisqoq Valley, the heart of the peninsula, and that it originally was farm lands, and woodlots and was a common area, and it sounded, to me, like you wanted to kind of bring that back as Common Area again for people to enjoy, almost like Ecotourism. To go in and experience the endangered species and the old growth forest. Do you think that is still something worth pursuing?

R: Yeah, of course. On the one hand, we want people to be back there and really understand, you know, what an incredible place we're living in here. On the other hand, we don't- you want to, want to-

T: We want to keep it protected?

R: Not trampling all over it! Keep it protected, you know. Let the animals and plants, you know, stretch their legs a little bit back there. But yeah, absolutely. And well, the commons in my time, when I was a kid, the area back there was referred to as the commons by the, well, it was mainly a farming community in those days. Which was only fifty years ago, when I was a teenager. And, yeah, it was called the commons because the farmers would take their cattle, their young cattle that they weren’t milking, back there in spring, I guess. And they would brand their cattle. Cruel in retrospect, perhaps, but they would brand their individual cattle and then they just let them all the run around loose back there. Which, may not have been best for the endangered plants and so on (laughs). But, and then in the fall, they’d go back and they chased them around and bring them back to their individual farms.

And of course it would be, you know, sometimes there would be disputes about, well, you know, “that's not your brand, that's my brand,” so on and so forth. And then there was a lot of very small-scale logging. Most of the local farmers would be, you know, one saw and horses, early on, of course. Or, you know, the small farm tractors to cut fence posts and firewood, that sort of thing. Very, very small scale.

T: When would you say that kind of ended? Or did it?

R: Well, I can say, in the case of our farm, that would have pretty well ended in the mid-60s. But, yeah. I mean, there's a few others like, you know, Alan Palmer, I think is still probably doing some of that. In fact, I happened to stop by, I was passing by on my bicycle, just as an aside, a couple of weeks ago on a Sunday morning. And I noticed that Alan is out there, tossing square bales up, like this, up onto his elevator in the haymow of his barn. I noticed he had some stacks of fresh cut lumber. So eventually he shows me this lumber mill, a sawmill that he built, which is just amazing. So he's cutting and sawing a bit of lumber, still.

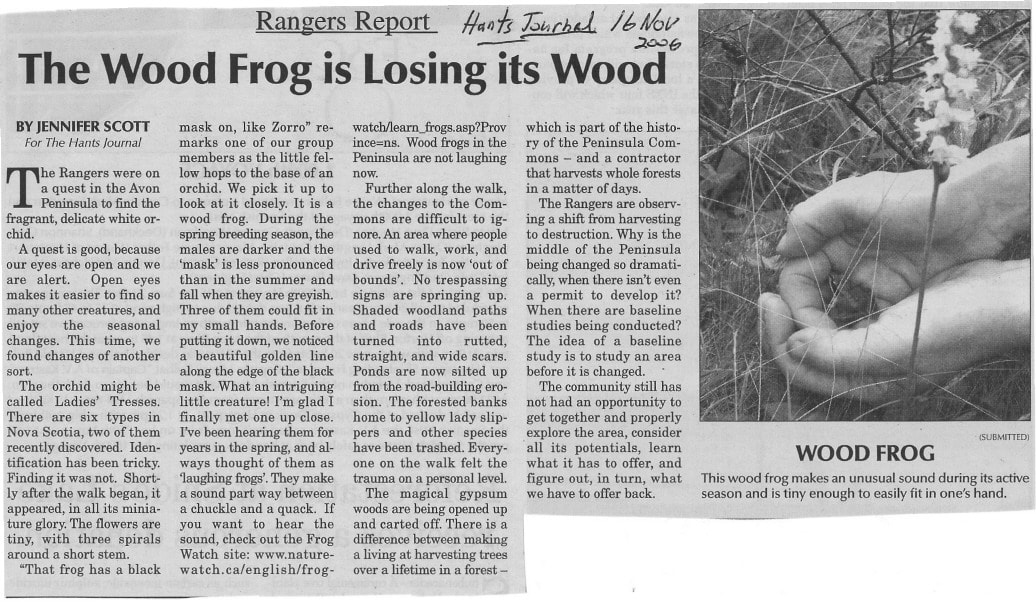

But this aspect about, oh, yes, about getting more back in the watershed. Of course, back around the the spring of 2006 -2007 around then, Jennifer Scott had organized what we called the Peninsula Rangers walks. So yeah, and their write-ups, I didn't come across some, I might be able to find them, but she was doing lovely write-ups of our walks, which were published somewhere, maybe the Hants Journal at the time. But yeah, we had every Sunday, or quite often, we had several of these walks where, you know, 15-20 community members would be led on a walk back there. And Jennifer and others would point out some of the flora and fauna and different characteristics; it was, yeah, it was pretty cool.

R: Yeah, of course. On the one hand, we want people to be back there and really understand, you know, what an incredible place we're living in here. On the other hand, we don't- you want to, want to-

T: We want to keep it protected?

R: Not trampling all over it! Keep it protected, you know. Let the animals and plants, you know, stretch their legs a little bit back there. But yeah, absolutely. And well, the commons in my time, when I was a kid, the area back there was referred to as the commons by the, well, it was mainly a farming community in those days. Which was only fifty years ago, when I was a teenager. And, yeah, it was called the commons because the farmers would take their cattle, their young cattle that they weren’t milking, back there in spring, I guess. And they would brand their cattle. Cruel in retrospect, perhaps, but they would brand their individual cattle and then they just let them all the run around loose back there. Which, may not have been best for the endangered plants and so on (laughs). But, and then in the fall, they’d go back and they chased them around and bring them back to their individual farms.

And of course it would be, you know, sometimes there would be disputes about, well, you know, “that's not your brand, that's my brand,” so on and so forth. And then there was a lot of very small-scale logging. Most of the local farmers would be, you know, one saw and horses, early on, of course. Or, you know, the small farm tractors to cut fence posts and firewood, that sort of thing. Very, very small scale.

T: When would you say that kind of ended? Or did it?

R: Well, I can say, in the case of our farm, that would have pretty well ended in the mid-60s. But, yeah. I mean, there's a few others like, you know, Alan Palmer, I think is still probably doing some of that. In fact, I happened to stop by, I was passing by on my bicycle, just as an aside, a couple of weeks ago on a Sunday morning. And I noticed that Alan is out there, tossing square bales up, like this, up onto his elevator in the haymow of his barn. I noticed he had some stacks of fresh cut lumber. So eventually he shows me this lumber mill, a sawmill that he built, which is just amazing. So he's cutting and sawing a bit of lumber, still.

But this aspect about, oh, yes, about getting more back in the watershed. Of course, back around the the spring of 2006 -2007 around then, Jennifer Scott had organized what we called the Peninsula Rangers walks. So yeah, and their write-ups, I didn't come across some, I might be able to find them, but she was doing lovely write-ups of our walks, which were published somewhere, maybe the Hants Journal at the time. But yeah, we had every Sunday, or quite often, we had several of these walks where, you know, 15-20 community members would be led on a walk back there. And Jennifer and others would point out some of the flora and fauna and different characteristics; it was, yeah, it was pretty cool.

| peninsula_rangers_reports.pdf | |

| File Size: | 1157 kb |

| File Type: | |

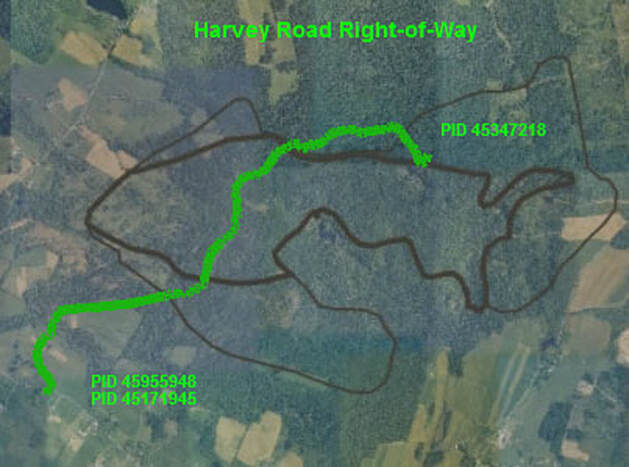

But that makes me think of one project that I would like to see, and I kind of wanted to see for a long time is the extension of our community trail back along the Harvey road and basically Into the heart of the Watershed, and across the so-called Baseline back there. And that land is owned by the Gypsum companies, as far as I know, still. But, my family's farm, which back in “Pioneer Days”, so-called, was the Harvey Farm.

T: Oh Okay.

R: And so there's a road, and the community trail today, the Westbrook Trail, is partially on that Harvey Road. Its the part that goes up into the woods beside the big field back there. And then, if you're going up the community trail, it takes a sharp, 90 degree turn to the left. But if you keep going, that's a continuation of the Harvey Road, which goes all the way back to a 50-acre woodlot, which actually belongs to the Harvey Farm, which is now Roseway farm.

T: Okay

R: And so, we've always contended that the Harvey Road is a right of way, that we have to have access to that wood lot. Otherwise there's no access to that property that we own.

So, that's something that, you know, that could happen if the energy were there to make it happen. And we actually have, we have more than a few dollars in the kitty, still, to help support that, or other activities that people might have in mind. But I mean, the road is still there, you could, basically, you can drive it on a 4x4 at the moment. Except I'm not sure exactly... the beavers have been back there, working their magic, so there might have to be a few workarounds. But yeah, a multi-purpose trail or a trail like the community trail as it is now, that reached right back there would be awesome, you know. Could be used for active transportation, picnics, you know, go back and see the Old Quarry workings from the period.

T: Oh Okay.

R: And so there's a road, and the community trail today, the Westbrook Trail, is partially on that Harvey Road. Its the part that goes up into the woods beside the big field back there. And then, if you're going up the community trail, it takes a sharp, 90 degree turn to the left. But if you keep going, that's a continuation of the Harvey Road, which goes all the way back to a 50-acre woodlot, which actually belongs to the Harvey Farm, which is now Roseway farm.

T: Okay

R: And so, we've always contended that the Harvey Road is a right of way, that we have to have access to that wood lot. Otherwise there's no access to that property that we own.

So, that's something that, you know, that could happen if the energy were there to make it happen. And we actually have, we have more than a few dollars in the kitty, still, to help support that, or other activities that people might have in mind. But I mean, the road is still there, you could, basically, you can drive it on a 4x4 at the moment. Except I'm not sure exactly... the beavers have been back there, working their magic, so there might have to be a few workarounds. But yeah, a multi-purpose trail or a trail like the community trail as it is now, that reached right back there would be awesome, you know. Could be used for active transportation, picnics, you know, go back and see the Old Quarry workings from the period.

This area in our Watershed had been worked some before the large industrial scale of mining that we’re more familiar with that we can see from the road around Mantua and gypsum mines towards Windsor. Which actually came to a halt because of... it may have been during the general strike.

T: The labor strike?

R: A labor strike. Yeah, and that's- I think that's when operations moved over to Wentworth.

T: Okay.

R: Near Windsor, not absolutely sure of that.

T: I think Carolyn's (van Gurp) is doing a little bit of research on that. So yeah. Maybe over the next year so we can help fill in the blanks there.

R: Yeah that would be... an interesting part of our history too, right? We don't hear so much about labor action these days, unless it's at Amazon. (laughs)

T: Wonderful. Is there any other information you think is important to include or…?

R: Well I look forward to having- you know, I appreciate the Museum's interest in maybe sort of digitizing or making available - more available - some of this history of the Watershed Society and that period of time in the community’s life.

I'd like to read these compelling vision statements.

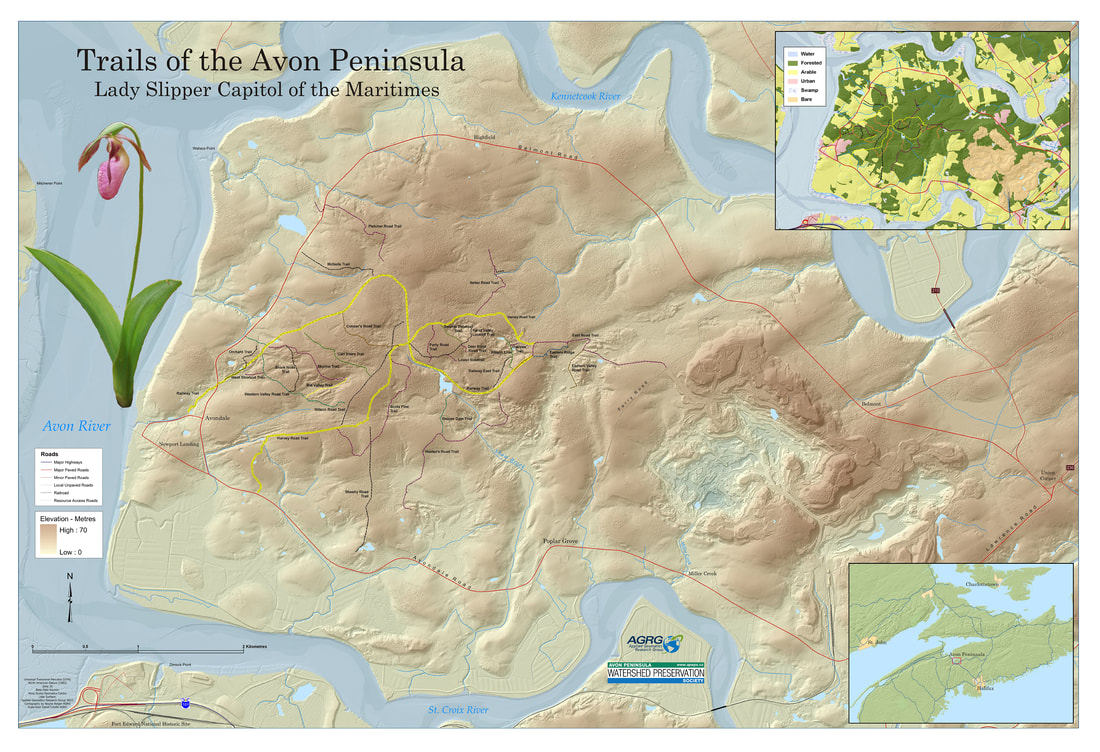

“the Avon Peninsula in Hants County Nova Scotias, bounded to the west by the Avon River to the South by the St.Croix River, and to the north by the Kennecook River, and to the east by the Lawrence Road”.

“Our watershed is where we live. It is like a neighborhood where all the plants, animals and people in our community share water. The watershed is the area of land that rain flows across or through on its way to our wells, wetlands, ponds, streams, marshes and tidal rivers”.

So that's what we kind of think of as the Avon Peninsula.

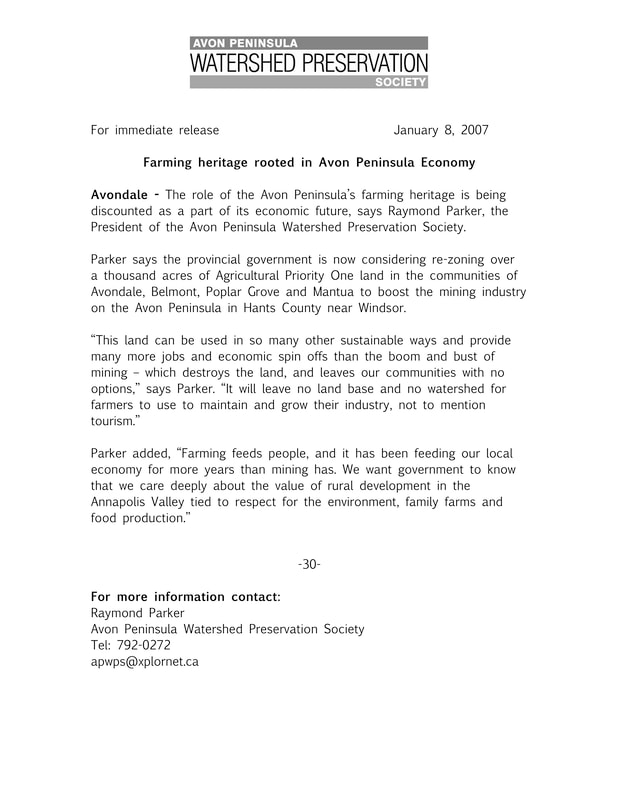

“The eastern part of the peninsula has been deeply impacted by strip-mining. However, the high, wooded land in the interior of the western part of the peninsula is still relatively intact. It is the heart of our watershed, as it is where the headwaters begin and where most of our wildlife habitat is. Underlying the heartland is one of the most complex gypsum karst geological formations on the planet, which gives rise to the fragile hydrology, unique ecology and very special landscape of the gypsum woods.”

And then it goes on to talk about the threatening specter of strip-mining.

Well, as it happened at the time, Jennifer Scott had been doing a lot of work with GPI Atlantic. Which is... GPI... ‘General Progress Indicators’. So, she was working on this massive project to develop an alternative way of doing economic assessment of projects or often economy, that, instead of just adding up dollars, actually looked at more qualitatively and put a value on things like community cohesiveness. Or, in fact, now this is starting to become a little more accepted I guess, though still not used, to look at net benefit as looking not just at jobs and you know, dollars per ton, or in our case, fractions of a cent per ton of gypsum we move. But to look at, what's it called? You know, ecosystem values and to actually to put dollar values on things like the capacity of a watershed to produce fresh water. Which otherwise, it just doesn't enter into economic calculations. So d’uh! We get a degraded planet.

So we worked, you know, and I was actually in... I’d returned from teaching at York University, in Toronto, in 2000 and taken up Organic Market farming. But I had studied, I went up there in, in '79, actually, to do a master's degree in Environmental Studies.

T: Oh Really?

R: Which included, you know, courses in environmental economics. So I was familiar with these concepts from then. So that, you know, this kind of perspective was informing our approach here as well.

Okay, the Vision. So I'll skip the core values. Vision.

“The potential watershed is valued as the core of our local ecosystem and is celebrated”- Choking up here, cripes- “and is celebrated as the natural Heartland of our community. It is comprised of a number of environmentally compatible land uses and is protected from incompatible residential, commercial and industrial development in perpetuity”.

This is our vision of the future.

“Our quality of life is protected and enhanced. The Integrity of the Peninsula Watershed ties together the community’s rural landscape, ponds, streams, wetlands, tidal rivers, scenic vistas, waterfront, heritage sites, farms, and homes. Net benefit is the key criteria of community planning. Economic and social renewal is rooted in an appreciation of our unique natural and cultural heritage. As with natural communities, economic and social vitality is best served by diversity. The way forward lies in a broad and self-generating approach to development rather than the cycles of dependence, inertia, environmental devastation, and economic decline that characterize resource extraction and single industry dependence.”

And then it goes on.

“Mission: to protect the ecological integrity of the Avon Peninsula and the commons watershed...” and so on and so on. “To promote local sustainable community development on the Avon Peninsula and work with other communities and organizations to promote watershed protection and local sustainable development in the region.”

Which, maybe I could just mention, the committee that I was responsible for was outreach to other communities and other organizations. So, at that- as it happened at that time, we were very fortunate to have a real mover and shaker in the Nova Scotia Environmental Network, Tamara, I think her last name was LorentzI, a real smart cookie and fearless. Tamara was organizing these tremendous multi-stakeholder meetings around the province and bringing in local organizations like our own and having face-to-face roundtable meetings with, you know, the department of environment and the department of natural resources. And that was just really tremendous because, you know, at any given time, there's, you know, there's us and Moose River, the communities up there were facing gold mining, for the gold mining projects. Serious environmental concerns there. There was coal mining in Cape Breton, groups there. There was a group up in Truro about the incinerators and burning of tires and incinerators. And also about spreading treated sewage on farmland for fertilizer, which was causing local health issues. And just like, wow, a lot going on. And as we speak, I think there's, there's always these issues. Well, you know, clear-cutting forestry policy and Nova Scotia, just yeah. Well, there's a lot, a lot to be said. And so, you know, an organization like the APWPS could be a real magnet for local people to do, really, you know, raise the voice, make a difference and it's also- it was a tremendous community building thing as well.

T: The labor strike?

R: A labor strike. Yeah, and that's- I think that's when operations moved over to Wentworth.

T: Okay.

R: Near Windsor, not absolutely sure of that.

T: I think Carolyn's (van Gurp) is doing a little bit of research on that. So yeah. Maybe over the next year so we can help fill in the blanks there.

R: Yeah that would be... an interesting part of our history too, right? We don't hear so much about labor action these days, unless it's at Amazon. (laughs)

T: Wonderful. Is there any other information you think is important to include or…?

R: Well I look forward to having- you know, I appreciate the Museum's interest in maybe sort of digitizing or making available - more available - some of this history of the Watershed Society and that period of time in the community’s life.

I'd like to read these compelling vision statements.

“the Avon Peninsula in Hants County Nova Scotias, bounded to the west by the Avon River to the South by the St.Croix River, and to the north by the Kennecook River, and to the east by the Lawrence Road”.

“Our watershed is where we live. It is like a neighborhood where all the plants, animals and people in our community share water. The watershed is the area of land that rain flows across or through on its way to our wells, wetlands, ponds, streams, marshes and tidal rivers”.

So that's what we kind of think of as the Avon Peninsula.

“The eastern part of the peninsula has been deeply impacted by strip-mining. However, the high, wooded land in the interior of the western part of the peninsula is still relatively intact. It is the heart of our watershed, as it is where the headwaters begin and where most of our wildlife habitat is. Underlying the heartland is one of the most complex gypsum karst geological formations on the planet, which gives rise to the fragile hydrology, unique ecology and very special landscape of the gypsum woods.”

And then it goes on to talk about the threatening specter of strip-mining.

Well, as it happened at the time, Jennifer Scott had been doing a lot of work with GPI Atlantic. Which is... GPI... ‘General Progress Indicators’. So, she was working on this massive project to develop an alternative way of doing economic assessment of projects or often economy, that, instead of just adding up dollars, actually looked at more qualitatively and put a value on things like community cohesiveness. Or, in fact, now this is starting to become a little more accepted I guess, though still not used, to look at net benefit as looking not just at jobs and you know, dollars per ton, or in our case, fractions of a cent per ton of gypsum we move. But to look at, what's it called? You know, ecosystem values and to actually to put dollar values on things like the capacity of a watershed to produce fresh water. Which otherwise, it just doesn't enter into economic calculations. So d’uh! We get a degraded planet.

So we worked, you know, and I was actually in... I’d returned from teaching at York University, in Toronto, in 2000 and taken up Organic Market farming. But I had studied, I went up there in, in '79, actually, to do a master's degree in Environmental Studies.

T: Oh Really?

R: Which included, you know, courses in environmental economics. So I was familiar with these concepts from then. So that, you know, this kind of perspective was informing our approach here as well.

Okay, the Vision. So I'll skip the core values. Vision.

“The potential watershed is valued as the core of our local ecosystem and is celebrated”- Choking up here, cripes- “and is celebrated as the natural Heartland of our community. It is comprised of a number of environmentally compatible land uses and is protected from incompatible residential, commercial and industrial development in perpetuity”.

This is our vision of the future.

“Our quality of life is protected and enhanced. The Integrity of the Peninsula Watershed ties together the community’s rural landscape, ponds, streams, wetlands, tidal rivers, scenic vistas, waterfront, heritage sites, farms, and homes. Net benefit is the key criteria of community planning. Economic and social renewal is rooted in an appreciation of our unique natural and cultural heritage. As with natural communities, economic and social vitality is best served by diversity. The way forward lies in a broad and self-generating approach to development rather than the cycles of dependence, inertia, environmental devastation, and economic decline that characterize resource extraction and single industry dependence.”

And then it goes on.

“Mission: to protect the ecological integrity of the Avon Peninsula and the commons watershed...” and so on and so on. “To promote local sustainable community development on the Avon Peninsula and work with other communities and organizations to promote watershed protection and local sustainable development in the region.”

Which, maybe I could just mention, the committee that I was responsible for was outreach to other communities and other organizations. So, at that- as it happened at that time, we were very fortunate to have a real mover and shaker in the Nova Scotia Environmental Network, Tamara, I think her last name was LorentzI, a real smart cookie and fearless. Tamara was organizing these tremendous multi-stakeholder meetings around the province and bringing in local organizations like our own and having face-to-face roundtable meetings with, you know, the department of environment and the department of natural resources. And that was just really tremendous because, you know, at any given time, there's, you know, there's us and Moose River, the communities up there were facing gold mining, for the gold mining projects. Serious environmental concerns there. There was coal mining in Cape Breton, groups there. There was a group up in Truro about the incinerators and burning of tires and incinerators. And also about spreading treated sewage on farmland for fertilizer, which was causing local health issues. And just like, wow, a lot going on. And as we speak, I think there's, there's always these issues. Well, you know, clear-cutting forestry policy and Nova Scotia, just yeah. Well, there's a lot, a lot to be said. And so, you know, an organization like the APWPS could be a real magnet for local people to do, really, you know, raise the voice, make a difference and it's also- it was a tremendous community building thing as well.

“This project has been made possible in part by the Documentary Heritage Communities Program offered by Library and Archives Canada / Ce projet a été rendu possible en partie grâce au Programme pour les collectivités du patrimoine documentaire offert par Bibliothèque et Archives Canada.”