Mi'kmaq of the Avon River

“Mi'kmaq” comes from a word meaning my friends; the original name for the Mi’kmaq was Lnu'k , meaning the people. Mi'kmaq and their ancestors, Sagiwe’k L’nuk (Ancient Ones), are the founding people of Nova Scotia and have been here for over 13,500 years. Before European contact, Mi’kmaq settled along all 42 principal rivers in this province, including the Avon River and its tributaries. The Avon River was part of an important portage route used by thousands of Mi'kmaq who travelled along the St. Croix River and Panuke Lake to cross the province.

Mi’kmaq spirituality and way of life has been based on respectful and sustainable use of natural resources. Mi’kmaq usually lived along rivers, spent summers along the coast, and winters inland to hunt. Up to 90% of food came from river and sea areas. Extremely skilled in hunting, and fishing, Mi’kmaq were able to carve out a relatively comfortable life until the arrival of Europeans. Mi’kmaq believed that Kluskap created the features of the land and taught them how to make earthenware, knowledge of good and evil, fire, tobacco, fishing nets, and canoes. The home of Kluskap is said to be Cape Blomidon, visible from the hills around this museum.

The Mi’kmaq Grand Council (Sante’ Mawio’mi) has been the traditional government, comprised of a Grand Chief (Kji Sagamaw), captains (kji’keptan) from each district, and wampum readers (putu’s) who maintain treaty and traditional laws. In the past, soldiers (smagn’is), who protected the people, also sat on the council. Leadership has been based on prestige rather than power. Consent of all, generally through a talking circle, has been the key to a peaceful existence.

Mi’kmaq traded with Europeans for centuries, providing them with the knowledge and resources needed to survive here, although the presence of colonial Europeans changed traditional Mi’kmaq lifestyle. Mi’kmaq, who respected others’ beliefs as well as their own, welcomed Catholicism into their lives and befriended the French at Port Royal in 1605. Marriage between Mi’kmaq and French or Acadians was common and each adapted to customs of the other.

Relations between Mi’kmaq and the British differed, especially after the 1713 Treaty of Utrecht, which did not consider Mi’kmaq tenure on the land. Peace and Friendship treaties negotiated between the Mi’kmaq and British between 1726 and 1761 did, however, recognize Mi’kmaq title and established rules for an ongoing relationship between nations. The Mi’kmaq did not surrender or cede rights to the land, and the treaties are still valid today.

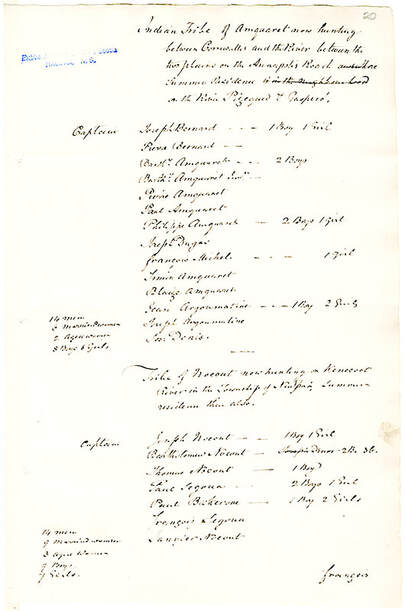

Mi’kmaq remained as autonomous people trying to accommodate the Europeans and adjust to the challenges they presented; however, the arrival of greater numbers of settlers created pressures on the Mi'kmaq. It’s estimated that by the 1700s, about three-quarters of the Mi’kmaq population was lost due to introduction of European diseases. A 1763 census, done just after arrival of the Planters, lists 51 Mi’kmaq, members of Nocoot (Knockwood), Segona, Briskarone, Thoma, and Michel families along the Kennetcook River.

The British tried to justify appropriation of Mi’kmaq lands by arguing that they did not cultivate or parcel the lands, that the land was “empty”.

From 1801 until the 1950s, Mi’kmaq were relocated to reserves, and, over time, much of the allocated reserve land was taken from them. In 1820, Shubenacadie (Sipekne'katik ) or Indian Brook Reserve was established as part of the attempted forced relocation. Today Sipekne'katik is the second largest Mi’kmaq band in Nova Scotia.

By 1855 all traditional Indigenous ceremonies were declared illegal. The 1876 “Indian Act” removed powers of self-determination and free movement; citizenship and voting rights were denied until 1961. In 1892, Indigenous children were referred to as “inmates” at Residential Schools. Attendance at these schools was mandatory for children 7 to 15 years of age, and parents were threatened with imprisonment if they did not send their children to the schools, which were designed to obliterate Indigenous culture. Nocoot descendent Isabelle Knockwood describes the conditions at the Shubencadie Residential School in her book, Out of the Depths.

Despite the pressures placed on them, Mi’kmaq resistance led to only about half the population being relocated to reserves. Today about 3% of Nova Scotia’s population is Mi’kmaq. There are 42 reserve locations and 13 Mi’kmaw communities in Nova Scotia, the largest being Eskasoni and Sipekne’katik. Up to 50% of Mi’kmaq now live in urban areas.

As recommended by the 2015 Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, we support the renewal of treaty relationships based on mutual recognition and respect, and shared responsibility for maintaining those relationships into the future. We are grateful for today’s work by Mi’kmaq who are protecting the waters of our rivers and Bay of Fundy from environmental harm and for the contributions of earlier Mi’kmaq who welcomed European settlers to their land and provided them with the knowledge and support they needed to survive. We recognize that this museum sits on unceded Mi’kmaq territory.

We are all treaty people.

Mi’kmaq spirituality and way of life has been based on respectful and sustainable use of natural resources. Mi’kmaq usually lived along rivers, spent summers along the coast, and winters inland to hunt. Up to 90% of food came from river and sea areas. Extremely skilled in hunting, and fishing, Mi’kmaq were able to carve out a relatively comfortable life until the arrival of Europeans. Mi’kmaq believed that Kluskap created the features of the land and taught them how to make earthenware, knowledge of good and evil, fire, tobacco, fishing nets, and canoes. The home of Kluskap is said to be Cape Blomidon, visible from the hills around this museum.

The Mi’kmaq Grand Council (Sante’ Mawio’mi) has been the traditional government, comprised of a Grand Chief (Kji Sagamaw), captains (kji’keptan) from each district, and wampum readers (putu’s) who maintain treaty and traditional laws. In the past, soldiers (smagn’is), who protected the people, also sat on the council. Leadership has been based on prestige rather than power. Consent of all, generally through a talking circle, has been the key to a peaceful existence.

Mi’kmaq traded with Europeans for centuries, providing them with the knowledge and resources needed to survive here, although the presence of colonial Europeans changed traditional Mi’kmaq lifestyle. Mi’kmaq, who respected others’ beliefs as well as their own, welcomed Catholicism into their lives and befriended the French at Port Royal in 1605. Marriage between Mi’kmaq and French or Acadians was common and each adapted to customs of the other.

Relations between Mi’kmaq and the British differed, especially after the 1713 Treaty of Utrecht, which did not consider Mi’kmaq tenure on the land. Peace and Friendship treaties negotiated between the Mi’kmaq and British between 1726 and 1761 did, however, recognize Mi’kmaq title and established rules for an ongoing relationship between nations. The Mi’kmaq did not surrender or cede rights to the land, and the treaties are still valid today.

Mi’kmaq remained as autonomous people trying to accommodate the Europeans and adjust to the challenges they presented; however, the arrival of greater numbers of settlers created pressures on the Mi'kmaq. It’s estimated that by the 1700s, about three-quarters of the Mi’kmaq population was lost due to introduction of European diseases. A 1763 census, done just after arrival of the Planters, lists 51 Mi’kmaq, members of Nocoot (Knockwood), Segona, Briskarone, Thoma, and Michel families along the Kennetcook River.

The British tried to justify appropriation of Mi’kmaq lands by arguing that they did not cultivate or parcel the lands, that the land was “empty”.

From 1801 until the 1950s, Mi’kmaq were relocated to reserves, and, over time, much of the allocated reserve land was taken from them. In 1820, Shubenacadie (Sipekne'katik ) or Indian Brook Reserve was established as part of the attempted forced relocation. Today Sipekne'katik is the second largest Mi’kmaq band in Nova Scotia.

By 1855 all traditional Indigenous ceremonies were declared illegal. The 1876 “Indian Act” removed powers of self-determination and free movement; citizenship and voting rights were denied until 1961. In 1892, Indigenous children were referred to as “inmates” at Residential Schools. Attendance at these schools was mandatory for children 7 to 15 years of age, and parents were threatened with imprisonment if they did not send their children to the schools, which were designed to obliterate Indigenous culture. Nocoot descendent Isabelle Knockwood describes the conditions at the Shubencadie Residential School in her book, Out of the Depths.

Despite the pressures placed on them, Mi’kmaq resistance led to only about half the population being relocated to reserves. Today about 3% of Nova Scotia’s population is Mi’kmaq. There are 42 reserve locations and 13 Mi’kmaw communities in Nova Scotia, the largest being Eskasoni and Sipekne’katik. Up to 50% of Mi’kmaq now live in urban areas.

As recommended by the 2015 Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, we support the renewal of treaty relationships based on mutual recognition and respect, and shared responsibility for maintaining those relationships into the future. We are grateful for today’s work by Mi’kmaq who are protecting the waters of our rivers and Bay of Fundy from environmental harm and for the contributions of earlier Mi’kmaq who welcomed European settlers to their land and provided them with the knowledge and support they needed to survive. We recognize that this museum sits on unceded Mi’kmaq territory.

We are all treaty people.